ALPHAVILLE (1965)

ALPHAVILLE (1965)

At a time when 10,000 of the world's leading physicists are holed up in a Swiss bunker engaged on a project that may one day enable them to pretend they understand the nature of the universe, Alphaville has never seemed more timely.

Jean-Luc Godard's film – "a science fiction film without special effects" in the words of the critic Andrew Sarris; "a fable on a realistic ground" in Godard's own description – is a cry of protest aimed at the worshippers of science and logic. Unlike Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which now resembles a picturesque relic of long-abandoned aspirations, Alphaville still seems to be watching the world come to meet it. And the world is very much closer to the director's creation than it was back in 1965.

To have seen it in its time – in my case at the Moulin Rouge cinema in Nottingham, which alternated the latest from Godard, Truffaut, Antonioni and Fellini with the creampuff-porn nudist flicks of the pre-Confessions era – was to have been astonished and delighted. The passage of almost half a century has done nothing to dim its stylishness, blunt its humour or extinguish its piercing message.

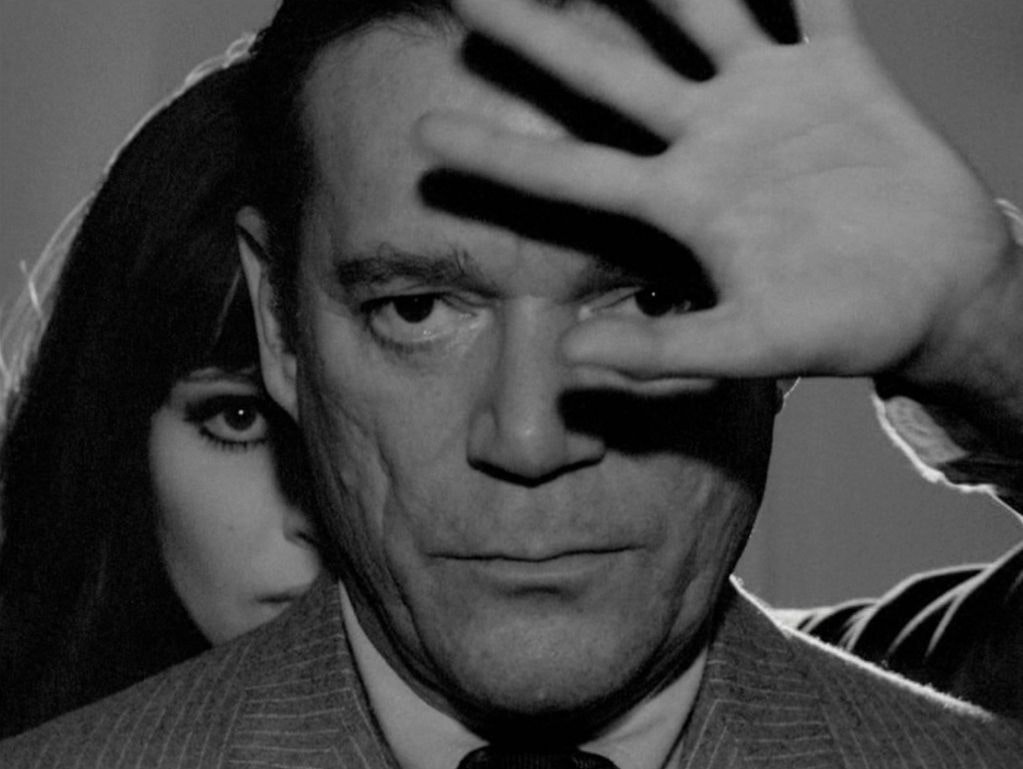

Eddie Constantine, the expatriate American actor, had already played the weatherbeaten FBI agent Lemmy Caution in several French films based on a series of novels by the British writer Peter Cheyney (sample titles: Dames Get Along and This Man Is Dangerous). Godard invited Constantine to reprise the role and sent Caution into the future, keeping the B-movie conventions intact along with his personal accoutrements – American car, Zippo lighter, raincoat, trilby, button-down shirt. Caution arrives in Alphaville on a mission to find a lost agent and assassinate Professor von Braun, the architect of a state whose people are ruled by logic and science and have been purged of emotion.

All the elements combine beautifully. Raoul Coutard's black-and-white photography turns everyday objects and settings – a hotel lobby, a swimming pool, a room full of mainframe computers, a jukebox, a Kodak Instamatic, the Paris suburbs at night – into the props of a convincingly dystopian futureworld whose philosophy is outlined in voiceover by the grating, inhuman tones of Alpha 60, the computer that regulates life in Alphaville. (Godard had the lines intoned by an actor who had lost his larynx and spoke through an artificial voice-box.) Paul Misraki's excellent score enhances moments of tension with warning stabs of low brass.

Anna Karina, meanwhile, is at her most darkly luminous as Natacha von Braun, the great leader's daughter. Her programmed responses slowly break down as the hardboiled detective gives his "pretty sphinx" a copy of poet Paul Eluard's Capital of Pain and introduces her to the concepts of "conscience" and "love" – words with which she is unfamiliar, since they have been progressively redacted from the dictionary that is the Bible of her father's totalitarian state. "Nearly every day, words disappear because they are forbidden," she tells him. "They are replaced by new words expressing new ideas." Orwell hovers around this film, along with Borges and Céline.

This was Godard's ninth feature film in six years, a rate of production resembling that of Beatles albums. There are signs of haste and improvisation, so Alphaville is much the better for its ability to make us think and trigger our feelings. At times it is a cartoon (the shootings, the use of negative images to convey disorientation) but at others it is more chillingly prescient than ever.

Yet Godard ends the piece on a note of romantic optimism, with Lemmy and Natasha escaping their pursuers and a dying world, fleeing to safety through intersidereal space (otherwise known as the Boulevard Périphérique) as the girl learns a new phrase: "Je vous aime ..."