NEXT SCREENINGS

Join us for a month‐long homage to the master of suspense. Our highlight: a curated run of Hitchcock classics, projected on genuine 16mm film in the intimate surroundings of The Castle Cinema.

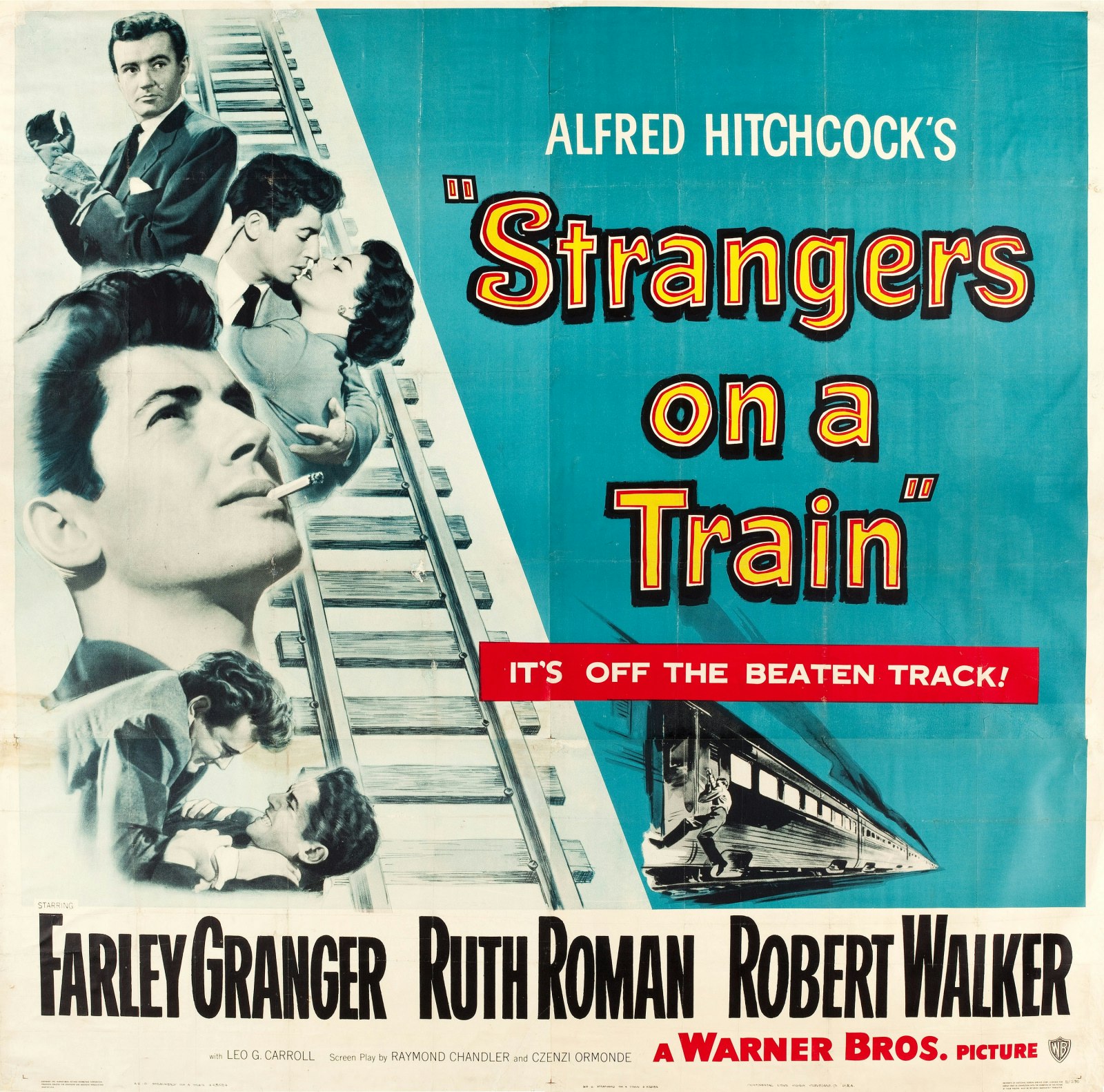

- Strangers on a Train (1951) (Thursday 20th Nov at 19:30 & Sunday 23rd Nov at 14:30) – A tense thriller of chance meetings and deadly bargains.

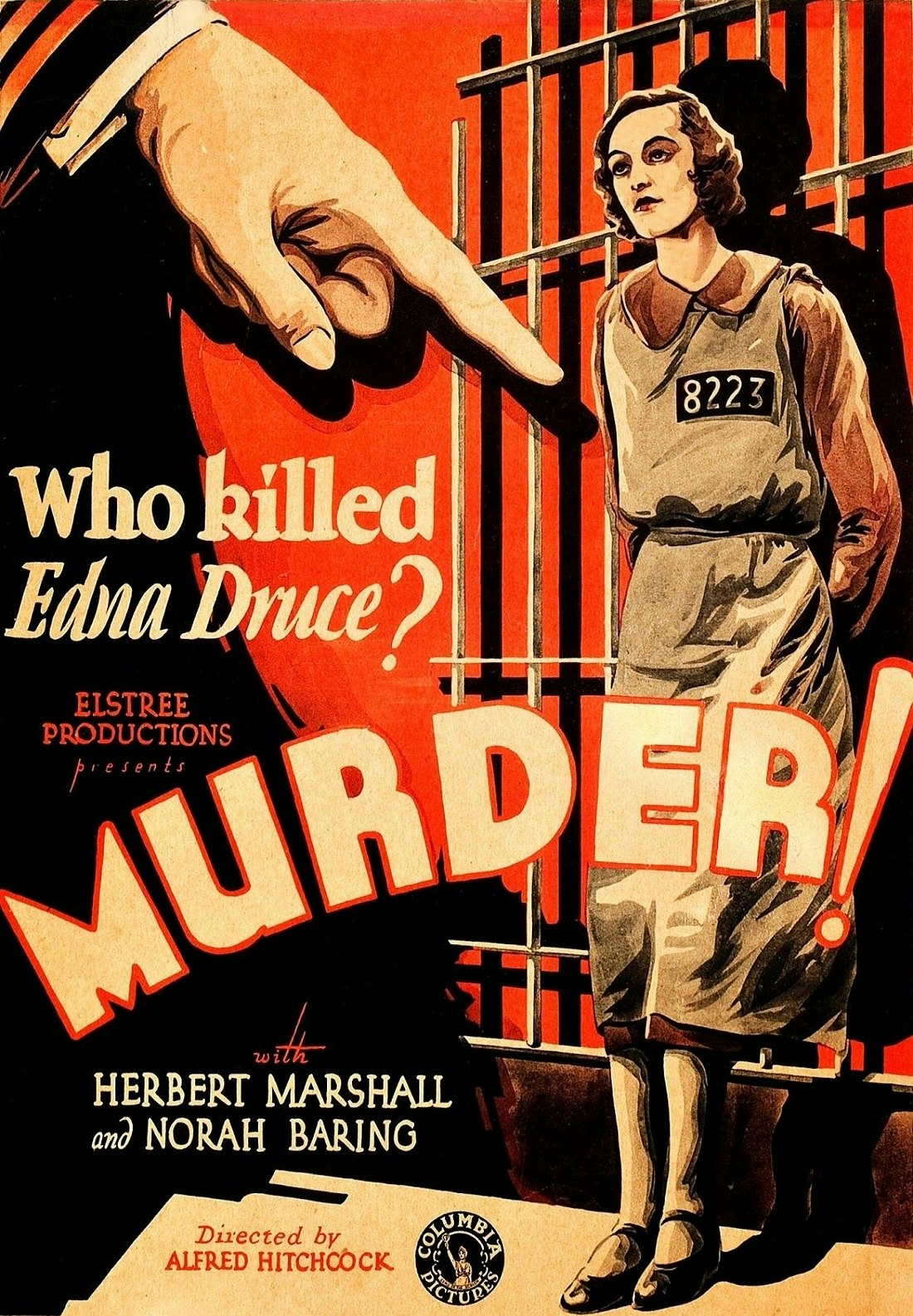

- Murder! (1930) — Wed 26th Nov at 19:30

STRANGERS ON A TRAIN (1951)

The abiding terror in Alfred Hitchcock’s life was that he would be accused of a crime he did not commit. This fear is at the heart of many of his best films, including “Strangers on a Train” (1951), in which a man becomes the obvious suspect in the strangulation of his wife. He makes an excellent suspect because of the genius of the actual killer’s original plan: Two strangers will “exchange murders,” each killing the person the other wants dead. They would both have airtight alibis for the time of the crime, and there would be no possible connection between killer and victim.

It is a plot made of ingenuity and amorality, based on the first novel by Patricia Highsmith (1921-1995), who in her Ripley novels and elsewhere was fascinated by brainy criminals who functioned not out of passion but from careful calculation, and usually got away with their crimes. The “criss-cross” murder deal in “Strangers on a Train” indeed would have worked perfectly — except for the detail that only one of the strangers agrees to it.

Guy Haines, a famous tennis player, is recognized on a train by Bruno Anthony, whose conversation shows a detailed knowledge of Guy’s private life. Guy wants a divorce from his cheating wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers), in order to marry Anne Morton (Ruth Roman), the daughter of a U.S. senator. Over lunch in his private compartment, Bruno reveals that he wants his father dead, and suggests a “perfect crime” in which he would murder Guy’s wife, Guy would murder Bruno’s father, and neither would ever be suspected.

Bruno’s manner is pushy and insinuating, with homoerotic undertones. Guy is offended by the references to his private life, but inexplicably doesn’t break off the conversation — which ends on an ambiguous note, with Bruno trying to get Guy to agree to the plan, and Guy trying to jolly him along and get rid of him.

But Bruno does murder Guy’s wife, and then demands that Guy keep his half of the bargain. As a plot, this has a neatness that Hitchcock must have found irresistible — especially since Guy has a motive to murder his wife, was seen in a public fight with her earlier on the day of her death, and even told his fiancée he would like to “strangle” Miriam.

Hitchcock said that correct casting saved him a reel in storytelling time, since audiences would sense qualities in the actors that didn’t need to be spelled out. Certainly the casting of Farley Granger as Guy and Robert Walker as Bruno is crucial. Hitchcock allegedly wanted William Holden for the role of Guy (“he’s stronger,” he told Francois Truffaut), but Holden would have been all wrong — too sturdy, too put off by Bruno (despite the way Holden allowed an aging actress to manipulate him in “Sunset Boulevard“).

Granger is softer and more elusive, more convincing as he tries to slip out of Bruno’s conversational web instead of flatly rejecting him. Walker plays Bruno as flirtatious and seductive, sitting too close during their first meeting, and then reclining at full length across from Guy in the private compartment. The meeting on the train, which was probably planned by Bruno, plays more like a pickup than a chance encounter.

It is this sense of two flawed characters — one evil, one weak, with an unstated sexual tension — that makes the movie intriguing and halfway plausible, and helps explain how Bruno could come so close to carrying out his plan. Highsmith was a lesbian whose novels have uncanny psychological depth; Andrew Wilson’s 2003 biography says she often fell in love with straight women, and her stories frequently use a buried subtext of unstated gay attraction — as in “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” made into a 1999 movie in which her criminal hero Tom Ripley falls in love not so much with his quarry Dickie Greenleaf as with his identity and lifestyle.

Although homosexuality still dared not speak its name very loudly in 1951, Hitchcock was quite aware of Bruno’s orientation, and indeed edited separate American and British version of the film — cutting down the intensity of the “seductiveness” in the American print. It’s worth noticing that Hitchcock also cast Granger in “Rope” (1948), based on the Leopold-Loeb case; it was another story about a murder pact with a homosexual subtext.

“Strangers on a Train” is not a psychological study, however, but a first-rate thriller with odd little kinks now and then. It proceeds, as Hitchcock’s films so often do, with a sense of private scores being settled just out of sight. His obsession with being wrongly accused no doubt refers to a traumatic episode in his childhood, when his father sent naughty little Alfred to the police station with a note asking the sergeant to lock him up until called for. Interesting, in this context, is Hitchcock’s casting of his own daughter, Patricia, as the outspoken young Barbara Morton, kid sister of Guy’s fiancée Anne. Patricia Hitchcock and Kasey Rogers look a little alike and wear very similar eyeglasses; Bruno is playfully demonstrating strangling techniques at a party when he sees Barbara, flashes back to the murder, and flips out. The kid sister gets the creepiest lines in “Strangers on a Train,” especially during an early meeting involving Guy and the senator’s whole family; she keeps blurting out what everyone is afraid to say.

Hitchcock was above all the master of great visual set pieces, and there are several famous sequences in “Strangers on a Train.” Best known is the one where Guy scans the crowd at a tennis match and observes that all of the heads are swiveling back and forth to follow the game — except for one head, Bruno’s, which is looking straight ahead at Guy. (The same technique was used in Hitchcock’s “Foreign Correspondent,” where all the windmills rotate in the same direction — except one.)

Another effective scene shows Guy floating in a little boat through the Tunnel of Love at a carnival; Miriam and two boyfriends are in the boat ahead, and shadows on the wall make it appear Bruno has overtaken them. In a scene where Guy goes upstairs in the dark in Bruno’s house, Hitchcock told Truffaut, he hit on the inspiration of a very large dog to distract the audience from what he would probably find at the top.

Then there’s the famous sequence involving a runaway merry-go-round, on which Guy and Bruno struggle as a carnival worker crawls on his stomach under the revolving ride to get to the controls. (This shot was famously unfaked, and the stunt man could have been killed; Hitchcock said he would never take such a chance again.) Another great shot shows Bruno’s face in the shadow of his hat brim, only the whites of his eyes showing.

Hitchcock was a classical technician in controlling his visuals, and his use of screen space underlined the tension in ways the audience is not always aware of. He always used the convention that the left side of the screen is for evil and/or weaker characters, while the right is for characters who are either good, or temporarily dominant. Consider the scene where Guy is letting himself into his Georgetown house when Bruno whispers from across the street to summon him. Bruno is standing behind an iron gate, the bars casting symbolic shadows on his face, and Guy stands to his right, outside the gate. Then a police car pulls up in front of Guy’s house, and he quickly moves behind the gate with Bruno; they’re now both behind bars as he says, “You’ve got me acting like I’m a criminal.”

The Robert Walker performance benefits from a subtle tense urgency that perhaps reflected events in his private life; he had a nervous breakdown shortly after filming was completed, was institutionalized for treatment, and died of an accidental overdose of tranquilizers. (Leftover closeups from this film were used to finish his final film, “My Son John.”) Although Hitchcock said in Francois Truffaut’s book-length interview that he didn’t much like either of the actors, Walker’s Bruno has been called one of Hitchcock’s best villains, and Hitch agreed with Truffaut that the audience sympathy was more with him than with Granger’s playboy.

The movie is usually ranked among Hitchcock’s best (I would put it below only “Vertigo,” “Notorious,” “Psycho” and perhaps “Shadow of a Doubt“), and its appeal is probably the linking of an ingenious plot with insinuating creepiness. That combination came in the first place from Highsmith, whose novels have been unfairly shelved with crime fiction when she actually writes mainstream fiction about criminals.

There’s an intriguing note from a user of the Internet Movie Database, claiming to have spotted Highsmith in a cameo in the film. She’s behind Miriam in the early scene in the record store, writing something in a notebook. No Highsmith cameo has even been reported in the movie’s lore (all the attention goes to Hitchcock’s trademark cameo) but you can look for yourself, in chapter six of the DVD, 12 minutes and 16 seconds into the running time. To think she may have been haunting it all of these years. ROGER EBERT (2004)

MURDER! (1930)

Hitchcock's third sound film, made in 1930 for British International Pictures, was a return to the crime genre, adapted from the stage play Enter Sir John written by Clemence Dane and Helen Simpson. The adaptation is credited to Hitchcock and Walter Mycroft.

Like Hitchcock's debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), and the later Stage Fright (US, 1950), Murder!'s action took place in a theatrical setting. Hitchcock was an enthusiastic theatre-goer, and one of Murder!'s most entertaining scenes takes place during the performance of a farce, when two detectives become increasingly confused as members of the cast come and go, dropping in and out of character.

The film contains a number of innovations, including what some believe to be the first use of a voice-over to denote an internal monologue. This in an unusual scene in which the theatre star turned detective, Sir John, ponders the case while shaving and listening to the wireless; Hitchcock claimed that for the radio music he used a live orchestra on set, rather than a recording.

One of Hitchcock's favourite plots, notably in The 39 Steps (1935), Young and Innocent (1937) and North by Northwest (1959), was the attempt of a falsely accused man to prove his innocence, often with the help of a woman. The plot of Murder!, however, is more closely related to Blackmail (1929) and (to a lesser extent) Sabotage (1936), in that the accused is female and is defended by a male associate. In those two films however, the women in question are guilty of murder - with mitigating circumstances - whereas in Murder!, Diana is entirely innocent but, for reasons of her own, is willing to accept the charge.

Although ostensibly the real villain of Murder!, Handel Fane (Esmé Percy) is driven to murder by the desire to hide his mixed-race origins, the film subtly implies that his true secret is homosexuality. Percy's performance is notably camp, and Fane first appears in women's clothing (although this is in the context of the farce in which the character is performing). In 1930, this is about as close as a mainstream British film could come to representing homosexuality on screen.

Hitchcock simultaneously shot a German language version of the film, with an almost completely different cast, released as Mary in 1931.

TO JOIN OUR MAILING LIST EMAIL US AT - info@cine-real.com

FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM - cinereal16mm