BEING THERE (1979)

BEING THERE (1979)

Among the sharpest of all satires, Being There, released in 1979, would be the last great film made by director Hal Ashby, who had the most extraordinary track record of any filmmaker of the 1970s. The novel by Polish-born author Jerzy Kosinski had been published in 1970, the same year that Ashby made his directorial debut with The Landlord. Over the next several years, Ashby made seven other classics of American counterculture cinema. His films such as Harold and Maude (1971), The Last Detail (1973), Shampoo (1975), and Coming Home (1978) made Americans rethink their attitudes toward politics, the Vietnam War, sexuality, and each other. Being There arrived at the end of the decade, after the rebelliousness and radical behavior of 1960s counterculture had subsided into the drugs and self-indulgence of the so-called “Me” generation of the 1970s. The most prominent symbols of the establishment were fading away: Richard Nixon had left the White House, the Vietnam War had ended, and several small victories had been won for racial equality and women’s rights. However, television had become so inescapable in the American home that life seemed almost impossible without its constant buzz. Worse, the rebels of the 1960s and the New Hollywood had sold out. But Ashby, ever the anti-authoritarian, had one more blow to strike against the systems of American politics, organized religion, and media culture.

Being There is the story of Chance, played by Peter Sellers in arguably his finest and most complex performance. Chance is a blank-minded, emotionally muted gardener. Television has been Chance’s only exposure to the outside world beyond the walled garden where he has spent his entire life. After the death of his wealthy benefactor, known only as the “old man,” with whom he has lived his entire life in isolation, Chance is forced onto the streets of Washington D.C. and, soon enough, finds himself struck by a limousine that belongs to one of the richest, most powerful men in the world, Ben Rand (Melvyn Douglas). Because he’s well-dressed in the deceased “old man’s” finely tailored hand-me-down clothes, Chance is mistaken for a well-to-do businessman. Rand’s wife Eve (Shirley MacLaine) misidentifies “Chance the gardener” as “Chauncey Gardiner,” a cipher who becomes everything to everyone he meets. He’s instantly trusted by men of power, including Jack Warden’s President of the United States, who takes Chance’s inane observations, which are nothing more than gardening tips and lines repeated from television programs, as insightful wisdom about grand economic and geopolitical concepts. And so, Chance finds himself in the position of a trusted political advisor and public figure, and before long, he becomes the next in line for the presidency.

Most of Ashby’s films center on disenchanted characters who rebel against systems of authority. Bud Court’s alienated teen in Harold and Maude acts out against his wealthy mother by staging fake suicides with grisly detail. The sailors in The Last Detail raise all sorts of hell, representing the lost innocence and hopelessness felt by many during Vietnam, while questioning the institutions that perpetuate it. Likewise, Jane Fonda sees the human toll of Vietnam in Coming Home, epitomized by Jon Voight’s disabled Vet and Bruce Dern’s ideologically crushed soldier. But rather than another story about rebels against the system, Being There finds Ashby exposing the stupidity and soullessness of American politics, television, religion, and racial hierarchies. His film is a portrait, not only of Chance’s comical and ironic journey to the White House but also the institutions that quickly put their faith in someone who tells them what they want to hear. Being There, more than any other film in Ashby’s career, seems to capture the director’s desire to make artistic, socially relevant films, yet do so in a way that entertains, even as it cuts into the establishment. It’s all the more affecting because the film was Ashby’s last effort before his decline into a downward spiral of drugs, anger, and ultimately, his death.

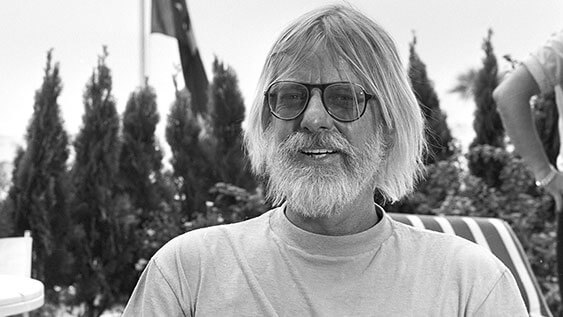

Ashby was not a movie brat like other counterculture filmmakers in the New Hollywood. He did not attend a prestigious film school like Peter Bogdanovich, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola did. Ashby was born in 1929 to a Mormon family in Utah. Being around farms in his youth exposed him to cruelty against animals, and from an early age, he became a vegetarian, a choice supported by his mother, “the original hippie,” as he called her. His father was another story. When Ashby was just 12, he discovered his father’s body in the family barn with a bullet hole located under his chin in an apparent suicide. Losing his father during the already tumultuous period of adolescence led to prolonged, unresolved conflict in Ashby, whose disposition was usually laid-back and empathetic. But he was also capable of outrageous bursts of anger from the emotion he bottled up about his father or, later in life, the social injustices he saw around him. That trauma, wrote biographer Nick Dawson, meant Ashby “struggled with issues about authority figures as well as fear of emotional closeness, abandonment, and betrayal.” In subsequent years, Ashby became known for ending relationships before he became too dependent on them. His first marriage ended when he was just 17. He would be married another four times throughout his life, and each marriage ended in divorce.

After a series of odd jobs in his youth, Ashby decided in 1949 to leave his first wife and child behind and head to Hollywood, but not before exploring his country. Living the life of a poor drifter, Ashby got to know America. He worked in various jobs, read books, and found himself. He worked as a salesman for a time, but he could not bring himself to lie to a customer to make the sale. Lies would later be the driving force behind Ashby’s suspicion of politicians and his antagonistic attitude toward Hollywood authorities. He despised lies, and he became known for telling the achingly honest truth, and with that came an emotional openness and vulnerability—something that emerges in his treatment of the characters from Harold and Maude to Coming Home. “A hippie before the word was coined,” wrote Dawson, “Ashby looked at the person, not the skin color, and was troubled by the unenlightened minds of most Americans.” He had a sensitive, decidedly liberal persona that came complete with a penchant for marijuana. Ashby, an avid drinker in his youth, gave up alcohol early in life; but he eventually earned the nickname “Hashby” for all the weed he smoked. Over the next several decades until his death, Ashby smoked pot on the regular. He would become known for his long, unkempt hair and bushy beard, but he was also fastidiously clean and germaphobic to the point of neurosis.

Before all that, Ashby arrived penniless in Hollywood and went to the State Employment Department. He asked for a job in motion pictures, which was not the usual way one gets into the movie business. He had always loved going to the movies, but the dream of Hollywood was less a personal ambition than a symbol of escaping his former life in Utah. Nevertheless, Ashby was given a job making copies at Universal, and while there, he quickly sized up the power dynamics. He set his sights on the best job around, and that was a director. Talking to several established filmmakers around the studio, Ashby was told that if he wanted to become a director, he should get into editing. With this, Ashby embarked on an eight-year apprenticeship to become a union editor. His career progress was slow, and it wasn’t until the mid-1950s that Ashby became an assistant editor, working closely under mentor Robert Swink on projects including George Stevens’ The Diary of Anne Frank (1959). After working on a number of productions, Ashby was encouraged by director William Wyler to contribute creative ideas during the post-production of the Western epic The Big Country (1958), and Wyler’s attitude of collaborative filmmaking inspired him, reinforcing the idea that he would develop into one of the many editors to become directors, such as David Lean or Robert Wise.

Ashby’s desire to become a director was put into jeopardy when he quit another assistant editing job under Stevens to serve as the chief editor on Tony Richardson’s The Loved One (1965), a job from which Ashby was fired because Richardson preferred his usual editor in England. After this brief streak of bad luck, he befriended director Norman Jewison, another rebel of the Hollywood system with a deep social conscience and an ingrained belief that films should improve the changing face of America. Jewison asked him to edit his new project, The Cincinnati Kid (1965), and over the next several years, Ashby and Jewison would remain together for The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! (1966); In the Heat of the Night (1967), which earned Ashby an Oscar for Best Editing; and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). Ashby and Jewison were beyond simpatico; they became close collaborators and intimate friends. It was Jewison who eventually asked Ashby what he wanted to do with his career, and Ashby responded that he wanted to become a director. Since they had already been developing an adaptation of Kristin Hunter’s 1966 novel The Landlord, which Jewison could not fit into his schedule anyway, he suggested that Ashby direct the project. It was around this time that Jewison, a Canadian who had become fed up with the trajectory of the United States, departed Hollywood to shoot Fiddler on the Roof (1971) in Europe. Without his mentor, Ashby was on his own to develop his directing career in Hollywood.

Unlike other New Hollywood filmmakers who emerged in an era obsessed with the auteur theory, thus making the director the star, Ashby preferred to remain out of the spotlight, even as he yearned for the complete creative control that he sometimes struggled to attain. Although The Landlord was not a strong box-office performer, its subject matter—about a privileged white man who buys an inner-city apartment building in a black neighborhood with plans to gentrify, only to instead become sympathetic to the residents—gained Ashby attention. He was offered the life-affirming Harold and Maude next, followed by the incendiary and highly regarded adaptation of The Last Detail, starring Jack Nicholson in an Oscar-nominated role. Both films demanded that Ashby fight with the studios to maintain the integrity of their stories, from the odd romance of the former to the sheer number of the word “fuck” in the latter. Ashby continued to work with some of the finest talents that emerged from the second half of the 1960s, often fighting to maintain artistic control amid demanding studios and producers. Among them was Warren Beatty on Shampoo (1975), the story of a womanizing hairdresser that Beatty had been trying to get made for years. Lee Grant won an Oscar for her supporting role, and the film earned two other nominations, but Ashby answered to Beatty on the set. Next came the Woodie Guthrie biopic Bound for Glory in 1976, a Dust Bowl drama nominated for four Oscars and winner of two. Though it diverts from fact, Bound for Glory contains the anti-authoritarian sentiments that define much of the director’s best work. What was implied in some of his earlier films came to the surface in Coming Home, the antiwar drama about disabled Vietnam veterans, which earned Oscars for Jane Fonda, Jon Voight, and the screenplay, plus another six nominations, including Ashby for Best Director.

All of this accounting of Ashby’s successes and award recognition serves only to demonstrate his incredible string of artistic and commercial hits throughout the decade, in which Ashby’s name became synonymous with a certain quality and rebelliousness in his filmmaking. Still, by the time Ashby became a director, he was a decade older than his New Hollywood contemporaries who went to film school and graduated on a directorial track. But Ashby was sure of the kinds of films he wanted to make; all of his years in the editing room and working alongside Jewison had given him time to ponder his artistic ambitions. He wanted to make films with a message but without preaching to his audience. Throughout the 1970s, most of Ashby’s films would have a sociopolitical undercurrent. The most unlikely example is Shampoo, a romantic farce that unfolds against the backdrop of Election Day in 1968, the year Nixon was elected—the irony being, Nixon was supposed to restore “law and order” after years of perceived cultural descent, a hypocritical notion given the Watergate scandal that was in the headlines during the film’s release. Dawson notes Ashby’s philosophy toward filmmaking: “You don’t do a film unless you want to make it, so once you have a real reason to do it, it will always be with you.” Ashby seems to have followed this line of thinking throughout the 1970s, whereas his work in the 1980s lost its edge. In the decade after his prime, he fell heavily into harder drugs, while his output was limited to airy commercial fare that resulted in uncharacteristic flops. Being There was the last great film made by Ashby. It might also be his best film, his funniest film, and his most searing indictment of American systems.

The project was first suggested to him when he was finishing work on The Last Detail. Peter Sellers had loved Harold and Maude and wanted to work with Ashby. He suggested that they adapt Kosinski’s novel, which Sellers had been obsessed with for years and struggled to get it made in Hollywood. He was drawn to the empty character of Chance, with whom he identified. But at the time Sellers suggested the project, Ashby had not yet achieved widespread recognition, and Seller’s career was in decline after a series of commercial disasters, so they could not raise the necessary interest to get Being There financed. Regardless, Sellers wanted to play Chance so badly that he had started working on the performance as early as 1973. He would act like Chance in public or remain in character during his frequent meetings with Kosinski over the years. Finally, at the end of the decade, after Ashby’s success with Coming Home, the director signed a deal with the production company Lorimar that gave him carte blanche over his next project. Ashby told Lorimar he wanted to make Being There with Sellers in the lead. But producer Andrew Braunsberg had a close association with Kosinski, and the author had a different vision for Chance; he wanted a younger actor, someone like Ryan O’Neal. And yet, because Bruansberg and Kosinski both wanted Ashby to direct, and Ashby insisted on working with Sellers given their discussions of the project from years before, they were stuck with Sellers. To appease Kosinski, who felt that Chance should be thinner and more attractive, Sellers arranged to have a facelift.

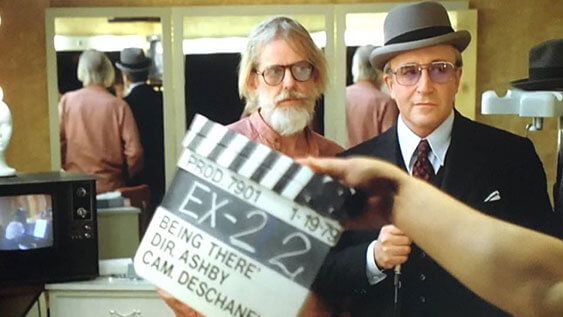

Despite Kosinski’s strong feelings about who should play Chance, he did not put equal care into adapting his book. Ashby felt Kosinski’s draft of the screenplay was unsatisfactory; it was too obvious, taking only the major brushstrokes of the story and none of its subtle comic tone. He hired Robert C. Jones, a longtime editor and the Oscar-winning co-writer of Coming Home, to do an uncredited polish that met with the author’s approval. Behind the camera, Ashby wanted his regular cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who was busy elsewhere, and so he turned to Caleb Deschanel who had just wrapped his first feature-length solo project on More American Graffiti (1979). Deschanel had worked behind the scenes in the camera and lighting department for Lucas, Coppola, and John Cassavetes, but two 1979 releases would earn him recognition from the National Society of Film Critics: Being There and Black Stallion. Ashby and Deschanel shot most of the film in Asheville, North Carolina, at the Biltmore Estate. Constructed by George Vanderbilt in 1895, it was the largest private home in the United States, complete with a 250 room mansion situated on 8,000 acres. Shooting commenced in January of 1979, and Ashby, who had earned a reputation as a difficult and demanding filmmaker since becoming successful, felt a new calm on the production according to Dawson. Perhaps it was because, for the first time in years under the Lorimar deal, he had more creative control than ever.

Sellers had thought about and obsessed over the role of Chance for years; he felt that he was Chance—something of a blank slate filled by his string of chameleon-like roles. But many of his recent performances by 1979 had earned Sellers a lousy reputation, and the early buzz about Being There was cynical. He had disappeared into dozens of caricatures, done a hundred voices, but none were so important to him as Chance. For the voice, he affected something between Stan Laurel and a mid-Atlantic inflection that, in its slow, deliberate performance, could be perceived as almost erudite depending on the context. On the set, Sellers remained in character, allowed only a few reporters to observe the shoot, and disappeared into his trailer between takes. Among his odd behaviors to maintain his headspace as Chance, Sellers also had other eccentricities, notes biographer Ed Sikov, such as refusing to work with anyone wearing the color purple. MacClaine had her curious behaviors too; she talked endlessly about spirituality, numerology, and past lives. Add to this Ashby’s omnipresent use of marijuana, and the set of Being There must have been a wild place. But it was a supportive shoot that fostered creative ideas, experimentation, and laughter. Sellers’ inability to perform a line of dialogue without breaking character in a fit of giggles meant Ashby had to cut the scene. Regardless, he was so impressed and tickled with Sellers’ talent that he included the gag reel footage over the end credits.

Ashby was always ahead of the curve in terms of the audience’s taste. When he released Harold and Maude, it flopped because viewers at the time refused to accept a story in which a young man falls in love with an octogenarian. Variety famously panned the film, saying it “has all the fun and gaiety of a burning orphanage.” But audiences eventually warmed to the idea, and over the subsequent decades, it transformed from a cult classic into a widely accepted masterpiece. Beau Bridges, star of The Landlord, told Dawson that Ashby had “a bizarre, crazy sense of humor that people weren’t ready for.” Bridges added, “He would talk about the world, and he could say, ‘Let’s burst this fucking bubble! And let’s do it with a joke.” These remarks underscore how Ashby recognized the injustices and authoritarian crimes occurring around him, and he sought to expose them, yet he would do so with humor. The same level of rebellious humor found its way into Being There, beyond the basic concept of the story. In the script, the film ends as Eve finds Chance walking in the woods, and the two declare that they have been looking for one another. She leads him to a limousine, and they drive off. But Ashby had another idea, something crazy and impulsive. He wanted Chance to walk on water.

Ashby arranged for a platform to be submerged under a half-inch of water so Sellers could walk out, and it would appear Christ-like. Sellers added to the idea, improvising the moment where Chance stops, gently dunks his umbrella in the water to confirm, yes, he is standing on the water’s surface, and then continues to walk. Many in the film’s cast and crew balked at the religious imagery Ashby meant to evoke, including MacClaine. But the scene’s meaning is ambiguous, if pregnant. Does the imagery imply that Chance is a godlike figure and that God is, ultimately, an unthinking moron like Chance? Is Chance a symbol of America’s willingness to put blind faith into someone who obviously has no clue? Or is he nothing more than a holy fool, an innocent who is nonetheless touched by God? It’s entirely possible that if Ashby were alive, he would say he did not know what he meant to evoke, that it’s up to the viewer to decide. Watching the film today, its message seems to reflect a condition in politics and religion present both then and now, where those seeking answers find only what they want to see, a process that requires all manner of mental gymnastics and justifications. Is Chance any different from Ronald Reagan, the actor-turned-politician who became the U.S. President in 1981 yet was caricatured as a witless puppet? And today, one cannot watch Chance without thinking of Donald Trump, a nincompoop who says whatever comes into his mind, often repeating lines he heard on television to the delight of followers who dote on every last word. No matter the time in history, the ideas behind Being There remain prescient.

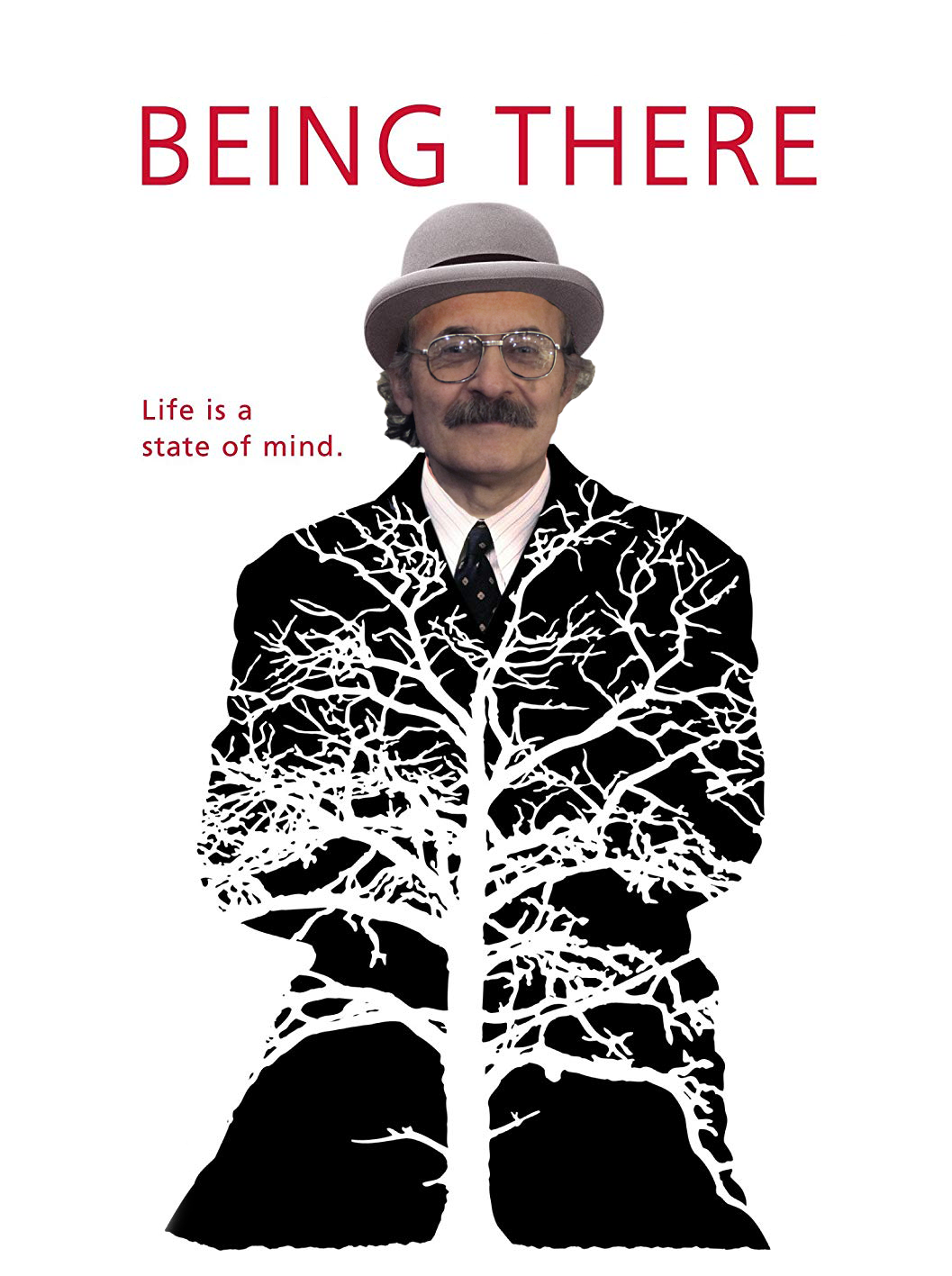

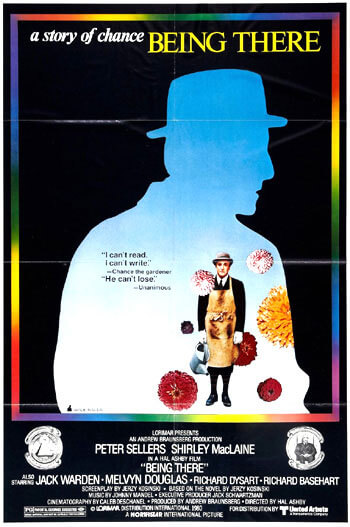

The notion of Chance as an empty suit is extended by his appearance in a homburg hat, both in the film and in its promotional material. It’s an image recalling René Magritte’s 1964 painting The Son of Man, where a man’s face is covered by a green apple, as well as several other Magritte paintings in which average, sometimes faceless men appear in the formal headdress. Magritte sought to comment on the increasing indistinction between individuals, especially among the wealth- and power-seeking bourgeoisie, by representing them as interchangeable. None is more relevant to Being There than his 1966 work Decalcomania, where a man in a bowler hat, the less formal cousin of the homburg, faces the sea, and beside him, a red curtain bears his empty cutout in negative space—the implication being that such a man is a transparent nothing. Even Being There’s theatrical poster seems to channel Magritte’s painting Golconda from 1955, a depiction of hundreds of identical bowler-hat-wearing men floating around nondescript buildings. The figures have no identity of their own, just a group association. Similarly, the poster’s image shows Chance floating in the air amid puffy Magritte-style clouds, facing the Biltmore Estate. He is a nothing, and yet he earns the respect of every authority figure he meets.

How does such a garden-variety man achieve power? Ashby, ever the social justice warrior, hints at another reason for Chance’s ascendance early in the film, just after the gardener takes his first steps onto the streets. As Chance walks through a largely African American neighborhood, the viewer cannot avoid seeing a graffiti message spray-painted onto a building wall: “America aint shit cause the white man’s got a god complex.” There’s something to be said about how the men of power in Being There, from Ben Rand to the President, trust Chance simply because he appears well-dressed, a man of mystery and means—but most importantly, he’s white. When Chance eventually appears on television and gives an interview where the American public clings to every dippy word out of his mouth, Ashby cuts away to Louise (Ruth Attaway), the African American servant who raised him. “It’s for sure a white man’s world in America,” she remarks. “Hell, I raised that boy since he was the size of a pissant… Had no brains at all… And look at him now! Yessir, all you gotta be is white in America and you get whatever you want!” Lines such as this harken back to Ashby’s collaboration with Jewison, specifically In the Heat of the Night and The Landlord, where they sought to made entertaining films with a message not just in favor of civil rights but condemning of white systems of power.

Ashby and Kosinski also meant Being There as a critique of television culture, where people glued to the idiot box no longer engage with the world, turning their brains into mush. Wexler had already censured the news media in 1969 with Medium Cool, the country was rattled by Sidney Lumet’s jab at television with Network in 1976, and Albert Brooks’ Real Life questioned the veracity of “reality TV” just a few months earlier in 1979. Being There was the latest attack on how TV was reshaping American minds and rendering people into uncritical, unfeeling zombies. Kosinski believed television “insulates people from direct encounters with others, deters self-reflection, and implies a false sense of control.” Though many who watch the film today explain Chance’s condition on a developmental disorder such as autism, the film implies that TV is responsible for Chance’s stunted growth. Ashby despised television as well, and he uses snippets and clips in the film to demonstrate its vacuousness, which in turn shaped Chance into the empty-minded person he is. At one point, the President’s Secret Service men say they ran Chance’s voice through an analysis machine and came up with no discernable origins, and then Ashby cuts to Chance engrossed in an episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and it becomes evident where Chance learned to speak. After all, the first scene shows Chance in bed, awakened when the television turns on by itself. Although probably set with a timer as Chance’s alarm clock, when the TV comes on, it serves to demonstrate the sole reason Chance gets up in the morning.

Chance’s television-shaped non-personality allows him to become a cipher when he interacts with the Rands and their employees. When Eve brings Chance home to care for him after her limo back into him, the dying billionaire Ben regards Chance’s “admirable balance,” and perceives his remarks about gardening as an elaborate business metaphor, perhaps only because he must find someone to replace him. Eve, facing Ben’s inevitable death and feeling neglected because of his illness, finds Chance to be “intense” and sexually mysterious, observing, “He’s such a sensitive man, don’t you think?” Whereas the butler, Wilson (Richard Venture), finds Chance’s remarks about riding in an elevator to be evidence of his dry wit. Likewise, Ben’s personal physician, Dr. Robert Allenby (Richard Dysart), believes Chance has a ripe “sense of humor”—but then, Allenby grows suspicious and, after talking with Louise, realizes that Chance is nothing more than a child’s mind in a man’s body. But Chance’s way of “keeping it at a third-grade level” is exactly how he unknowingly manipulates politicians and reporters. His rather Trumpian strategy with the press, when he confesses “I do not read papers; I watch TV,” earns his approach compliments for being honest and refreshing—qualities that ultimately lead to the clandestine organization that runs Washington D.C. selecting Chance as their next leader. No wonder the Soviet Ambassador (Richard Basehart) compares Chance to Ivan Krylov (1769-1844), the Russian satirist who wrote fables, often about animals, to reflect political conditions in his country. The way Chance speaks about the garden as it relates to the economy is worthy of a “Krylovian” tale.

Television, combined with his isolation in the same house for his entire life, has also left Chance ignorant to matters of race and sex—topics that were rarely discussed in any detail in the early decades of broadcasting, and therefore are foreign to Chance. His only exposure to people of color is Louise, and he associates her with lunch, so when he finally takes to the streets, he asks the first black lady he sees if she will fix him a meal. And when a gang of black teens pulls a knife on him, Chance attempts to change the channel with his remote, entirely unaccustomed to negative experiences in daily life. His experience with sexuality, meanwhile, remains something limited to the passionate kissing appropriate for television. In one of Being There’s funniest scenes, Eve comes onto Chance, who, imitating the delirious kissing scene from The Thomas Crown Affair on television, embraces her. When she wants something more, he replies flatly, “I like to watch,” referring to TV. Eve takes this to mean she should masturbate beside him and he will watch. As she does, Chance’s attention drifts back to the television set, where he begins imitating a yoga program.

However comical such scenes may be, Being There does not limit Chance to a mere joke. Take how Chance processes the two deaths in the film. Early on, after his “old man” benefactor dies, Louise tells him the body was cold. He looks at the body of the man who adopted him, touches the forehead to confirm that, sure enough, it is cold, and then sits down to watch television. He repeats this gesture after Ben’s death, acting out a scene that, to Allenby, looks no different than the common behavior of mourners who feel compelled to touch the deceased one last time. But it’s more than just Chance repeating a behavior. His eyes swell with tears, perhaps thinking about the “old man,” or perhaps feeling genuine grief for Ben. “He’s gone, Chauncey,” says Allenby. “Yes Robert,” replies Chance. “I have seen it before. It happens to old people.” It’s a rare moment that shows Chance processing his emotions, and without it, Being There might seem like a cold and cruel film that uses the character as the butt of a joke, rather than its device. Instead, what happens to Chance in his rise to the White House becomes a joke on the country. Chance is simply an innocent and misunderstood man, whereas the unthinking country that will elect him is far more ignorant, trusting, and unskeptical of their politicians and the influencers on TV.

Despite the potent commentaries throughout, Being There is Ashby’s most subdued film, formally. Deschanel’s camerawork is recessive and straightforward, allowing Seller’s performance and the film’s ever-present comic irony to induce laughs. The comedy often emerges through visual juxtapositions that do not overemphasize the comedic point. Only the final shot of Chance walking on water extends the film into comic gag territory, whereas the remainder of the film relies on the ironic misunderstandings between, well, everyone and Chance. Johnny Mandel, who had worked with Frank Sinatra and Barbra Streisand, composed the mysterious piano score that quietly and hypnotically invites the viewer to uncover the riddle of Chance. Mandel’s score suggests that something enigmatic, almost mystical, is happening before our eyes. Elsewhere, Eumir Deodato arranged the film’s most expressive and playful comic flourish with the jazzy disco riff on Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra.” The familiar music plays over Chance’s initial emergence into the outside world, a winking nod to its use in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which had established the music into the zeitgeist as a signifier of a transformative moment in human development. Just as Kubrick raised the frame to regard the alignment of the Sun, Earth, and Moon to this music, Ashby does something similar when he regards Chance walking toward the United States Capitol.

Upon its release in December of 1979, the responses to the film were almost unanimously enthusiastic. Being There performed well at the box-office and received glowing reviews from the major critics such as Andrew Sarris, Roger Ebert, and Vincent Canby. Douglas went on to win the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, but when Sellers was passed over for a Best Actor statue, he blamed Ashby’s inclusion of the end credits scene that shows Sellers corpsing, thus demystifying Chance. Though Being There was, arguably, the highest peak in Ashby’s career at that point, his decline over the next several years was not as gradual as his rise. With the onset of the 1980s, Ashby descended into a bout of eccentricity and paranoid behavior. His success and creative autonomy meant he could withdraw from his usual Hollywood circles and indulge in his newly acquired control and hardcore drug habit. He added cocaine and heroin to his intake, and a series of bad business deals led to many uninspired films throughout the 1980s. His behavior even lost him the chance to direct a passion project, Tootsie, which went to Sydney Pollack instead. By 1988, Ashby would be dead at 59 from pancreatic cancer, and many felt that Being There was the last and brightest example of the director’s talent. The scene of Chance walking on water was the final image from his films shown at his funeral.

Being There is Hal Ashby’s at once cynical view of America and hope for something better and more transcendent. When Ben Rand dies in the final scenes, he’s buried in a small pyramid on his land, at the top of which is an Eye of Providence, followed by the words, “Life is a state of mind”—the echoing last line of the film. The Eye, enclosed within the triangle of the Trinity, is an image used in both Christian and Freemason symbolism, denoting the presence of God looking over all things. Ashby’s film pokes a finger in that eye, suggesting that no such grand order to the universe can come from the systems in which people place their faith; they have no more certainty behind them than the insipid programs on television. Chance, meanwhile, lives his life as a vegetable, either as a plant in the garden or an enrapt viewer of television, the sleeper’s paradise. His new life is an alternative state of mind, far removed from the electronic modes of communication to which he is accustomed. It is a new condition where his perspective has become three-dimensional and achieved an ultra-realism, where the possibilities are endless. In this new reality, he can become President of the United States; he can walk on water. Ashby’s film exposes the oppressive machines of politics, religion, and technology, and it hopes that we see the possibilities beyond them. This seems to be the resounding sentiment of all Ashby’s films. Being There aims to snap the viewer out of their vegetative state, compelling us to choose an alternative, limitless state of mind.