DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954)

DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954)

Note: The following review discusses the anatomy of one crucial scene, but does not give away the ending to the film.

In the early 1950s, Warner Bros. had gone crazy for 3-D, and mogul Jack Warner wanted Alfred Hitchcock to experiment in the effect. Hitchcock, of course, had been experimenting in film style for years: the long-take, highly specialized and wholly unique camera movements, confined quarters, unreliable narrators, etc. It seem like the director who would seemingly try anything would embrace the opportunity to work with new technology, but he was smart enough to tell the difference between cinematic possibility and fleeting fad.

Despite his healthy skepticism, he signed on to produce Dial M for Murder utilizing the 3-D effect, chiefly because he knew fulfilling a certain favor could keep the shifty eyes of the studio off his back and let him work uninterrupted. In the fall of 1952, while in New York, he had seen British playwright Frederick Knott's stage play of the same name, about a man who plots to have his adulterous wife murdered in order to secure her hefty fortune. The murder goes awry, and the husband has to cover up his steps – the kind of story right up Hitchcock's alley. And, to add icing to the cake, Cary Grant was interested in playing the husband.

But like the murder itself, things began to slide off the tracks from the very beginning. The budget for Dial M for Murder was extraordinarily tight, and nearly all of Hitchcock's concessions were due to money. Warner vetoed filming on location in London (he didn't want the studio's only 3-D camera traveling overseas), and Warner vetoed Grant (too expensive, plus he claimed audiences wouldn't buy the shift away from lighter fare, which completely ignores Suspicion and Notorious). Production had to begin quickly and end quickly, so there was no time to get into Knott's play and re-tool it extensively for a cinematic rebirth, which left the setting to be very much a "stage." And even though Hitchcock had lost Grant, there still wasn't room in the budget for the lead actress to be anyone greater than a virtual unknown.

Yet what makes Hitchcock great is that when things began to slide away from him, nine times out of ten he could get away with it nevertheless. Dial M for Murder isn't among his banner productions, and it's only referenced in passing in his interviews or writings on him, but it is a remarkable film in many ways, one of his abandoned darlings that teaches us a great deal about what kind of filmmaker he was and happens to be quite entertaining in the process. From a purely cinematic vantage, part of its immense joy is how little the story is changed from the original theatrical production and how Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks literally seem to stage a play. A filmed play is, technically, the best way to describe Dial M for Murder, although its triumph is that it doesn't feel like it. (Note how each time Hitchcock filmed something in a small, enclosed space – Lifeboat, Rope, Rear Window – he filmed it differently.)

With Grant out of reach, the lead role of former tennis star Tony Wendice went to Ray Milland, who in my opinion is perpetually underrated. Tony has left the sport at the request of his wife Margot (Grace Kelly, at the time still relatively unknown), and their marriage can't be described in any way as truly satisfying. Margot is unaware that Tony knows of a previous relationship she had with a crime writer named Mark (Robert Cummings, who played lead in Saboteur). Tony blackmails a former classmate of his going by the name Lesgate (Anthony Dawson, who played the same role in the New York stage production) to kill Margot. When Margot survives, Tony has to juggle Margot, Mark, and a curious and determined inspector.

The story is tight, and overall the film is gripping, if not slightly long. Milland is grand and meticulous, even though Cummings is ... well, Cummings. In the twelve years that passed between Saboteur and Dial M for Murder, Cummings didn't become spectacularly telegenic, and when stacked against Milland, it's easy to tell which of the two had won an Oscar for Best Actor. The real draw to Kelly, who is lovely in Technicolor, in her first of three consecutive Hitchcock roles. Margot doesn't have as prominent of a role in the play as Tony or Mark, so it does feel like there is a large empty space on screen sometimes when Kelly isn't there. (But that's what generally happens when a mesmerizing actor or actress isn't there.) Because of the small sets (and the 3-D process), it was necessary for the camerawork to be as nimble, and Dial M for Murder is a great example of a Hitchcock film where you can detect the director's slightest presence in every shot, particularly the ones that seem to explode across the screen with his typical and artful delicacy.

When Dial M for Murder premiered in May of 1954, Hitchcock's dismissive attitude of 3-D as a mere fad had proved clairvoyant. Almost as soon as it had exploded in popularity, it had imploded and shrunk away lusterless. Dial M for Murder only played in 3-D in selected theaters upon its first run, but subsequent revivals have brought it back to be shown as it was intended. I've never seen it in 3-D, and look forward to the day I might be able to, but what I've read about it normally concludes the same thing you'd be able to tell from the film being shown on your television at home: that Hitchcock used the technology carefully and judiciously, aiming mostly at creating subtle depth on the primary set of the Wendice house. Many objects (such as lamps and furniture) are placed in front of the camera and supposedly "pop." The one grand exception is during the attempted murder scene, where Margot struggles against Lesgate and suddenly reaches her hand out (and directly toward the camera) for something to fend him off, translating into the effect of her "reaching out into the audience." Even on a two-dimensional space, though, the violent jerk of her arm and hand is rather startling.

Although not as beloved as some of Hitchcock's other masterful films, I have a theory that Dial M for Murder is necessary viewing for anyone seeking to prove why the director is cited as among the best. There's a moment of luminousness where the pacing, the camera, the script, and the editing all merge together and form a cohesive and brilliant scene. It occurs in the moment of the attempted murder, and it's a tour de force sequence; although it appears so simple and elegant in execution, in terms of suspense and skill it matches the sophistication and complexity of any scene from Hitchcock's acclaimed masterpieces. The success of the moment alone makes me wonder why Hitchcock would prove so discursive on the subject of the film later in his life.

But first, to appreciate the sequence in all its cinematic glory, it's necessary to note here that Dial M for Murder was re-adapted in the late 1990s as A Perfect Murder, with Michael Douglas and Gwyneth Paltrow in the Milland and Kelly roles. The murder scene in that below-par film hinges on the shock of a masked man jumping out from off-screen and the ensuing violence as Paltrow fights him off – bogeyman stuff basically, the kind of stuff you might well expect in a thriller film. Yet consider what Hitchcock does with the same scene. There is a splendid trail of guilt dripping across the characters and into the audience that exists only under the watchful eye of Hitchcock. For all intents and purposes, Tony is the bad guy: he has planned his wife's murder (although she's not exactly an angel, either). But beginning with the sequence of the murder, Hitchcock slyly begins to toy with our allegiances. We can't help but root for Margot not only to live and be proven redeemed, but we also find ourselves rooting for Tony, as well, to have his plan be performed successfully, or at least get away with what he has done.

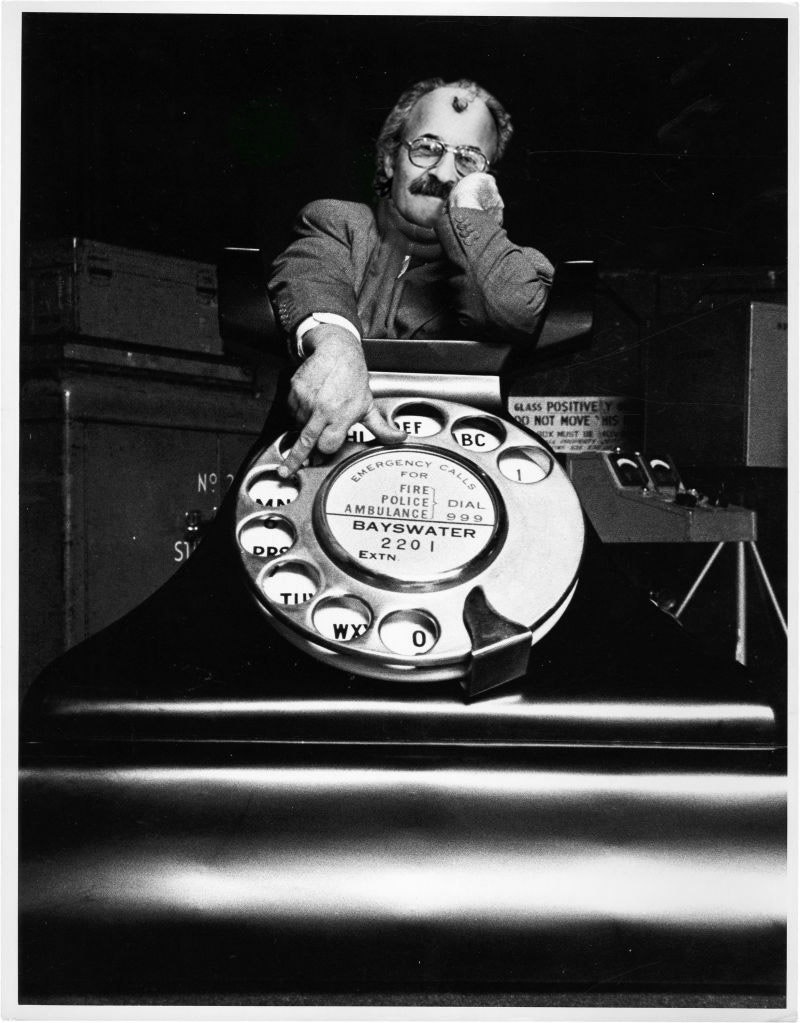

The attempted murder, which occurs roughly forty minutes into the film, has been plotted and spelled out for the audience in an earlier conversation between Tony and Lesgate. Tony is going to be out of the house and is supposed to call Margot at a specific time, and Lesgate will be waiting behind the curtain with a cloth to strangle her when she answers the phone. The scene begins with an anxious Tony, who is keeping a close eye on the time and realizes when his watch stops and he is late to call that he must have inadvertently overwound it. Lesgate, thinking the plan has been postponed, gets ready to leave. Tony gets up to go to the pay-phone to call Margot, and there's a steady shot of him walking through the lobby of the restaurant. He pulls the change out of his pocket and as he makes a slight left turn toward the pay-phone, the camera pans right to reveal someone else in the booth already. Dimitri Tiomkin's somewhat generic but highly effective tick-tock thriller score circles in the background, and Tony paces outside the booth, as frustrated now as we are. Once he gets into the booth, he slides in the coins and as the score booms thunderously, we are given an extreme close-up of the rotary phone, Milland's fingertip sliding into the number 6 spot (the "M"). Cut then to a seemingly unrelated shot of the mechanics inside the phone chirping and ticking away as the call is connected, but in the history of Hitchcock's films, we are given numerous shots of "behind-the-scenes" functionality (The Lodger, for example, includes a montage of how the newspaper is printed).

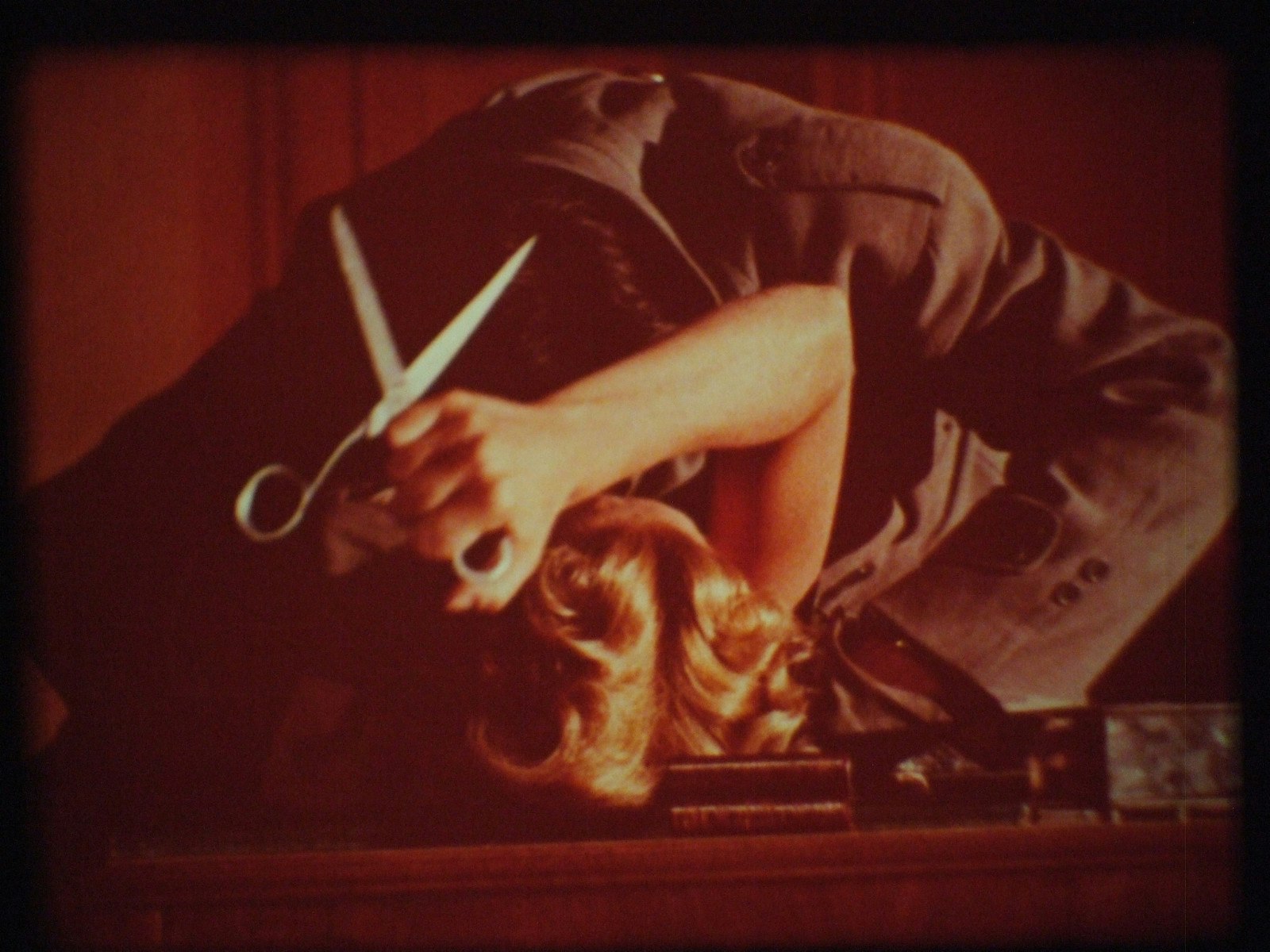

Back in the apartment, the phone rings. Lesgate, halfway out the door, turns around at its sound. The light snaps on in Margot's bedroom, visible between the door and the floor. She answers the phone in a three-quarter shot and slowly the camera begins to curl around her (she until eventually it staring at the back of her head, just as the Lesgate's cloth, pulled tight between his hands, comes into view. Smash-cut back to the front of her, Lesgate now positioned over her shoulder. The score has drowned out nearly all sounds but Margot repeating "Hello?" into the telephone and pressing the switchhook over and over. The orchestra crescendos as Lesgate finally attacks, with Margot panting and screaming and fighting; he pushes her onto the desk, a lamp breaking in the background – and this is where it gets really tricky – Milland now closes his eyes in what I suppose can only be called mournful (he has planned this, after all, so there's your Hitchcockian complexity). Kelly famously reaches back toward the camera, and grabs a pair of scissors left on the desk. Naturally, they are held stiff in the "X" position with the blades spread apart, and as the light gleams across the silvery metal, she stabs Lesgate in the back, a perfect moment of resistance and self-defense. Lesgate falls onto the floor, the scissors pressing deeply into him and killing him. Tony is stricken but unaware as he listens to the commotion on the telephone, then his eyes grow when Margot picks it up, sobbing and asking for the police.

"What's the matter?" he asks. She says she can't explain now and wants him to come quickly. But he prods her to reveal, unbeknownst to herself, the state of the plan: "Darling, pull yourself together. What is it?" And after she explains the attack, and he knows everything has gone wrong, the fear fills his face like water in a sponge. Although the words are by Knott, the response – utterly callous to Margot's well-being, but leading and hopeful the plan hasn't completely collapsed – is purely Hitchcockian in its dark humor, its duplicity, and its eagerness: "Did he get away?" She says the man is dead, and he tells her not to touch anything and he'll be home quickly.

Dial M for Murder is a 1954 American thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Ray Milland, Grace Kelly, and Robert Cummings. The movie was adapted from a successful stage play by Frederick Knott, and was released by the Warner Bros. studio.

The screenplay and the stage play on which it was based were both written by English playwright Frederick Knott, whose work often focused on women who innocently become the potential victims of sinister plots. The play premiered in 1952 on BBC television, before being performed on the stage in the same year in London's West End in June, and then New York's Broadway in October.

The single setting in the stage play is the living-room of the Wendices' flat in London (61A Charrington Gardens, Maida Vale). Hitchcock's film adds a second setting in a gentleman's club, the well of a staircase, a few views of the street outside, and a stylized courtroom montage. Having seen the play on Broadway, Cary Grant was keen to play the role of Tony Wendice, but studio chiefs did not feel the public would accept him as a man who arranges to have his wife murdered.

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten Top Ten" list—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genre—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Dial M for Murder was ranked the ninth best film in the mystery genre.[2]

The 1954 film was shot with M.L. Gunzberg's Natural Vision 3-D camera rig. This rig was notable for being the same rig that started the 3-D craze of 1953 with Bwana Devil and House of Wax. Intended originally to be shown in dual strip polarized 3-D, the film played in most theaters in normal 2-D due to the loss of interest in the 3-D process by the time of its release.[citation needed]

The film earned an estimated $2.7 million in rentals at the North American box office in 1954.

In February 1980, the dual-strip system was used for the revival of the film in 3-D at the York Theater in San Francisco. This revival did so well that Warner Bros. re-released the film using Chris Condon's single-strip StereoVision 3-D system in February 1982.

12 ANGRY MEN (February, 2019)