Le Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) (1960)

Le Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) (1960)

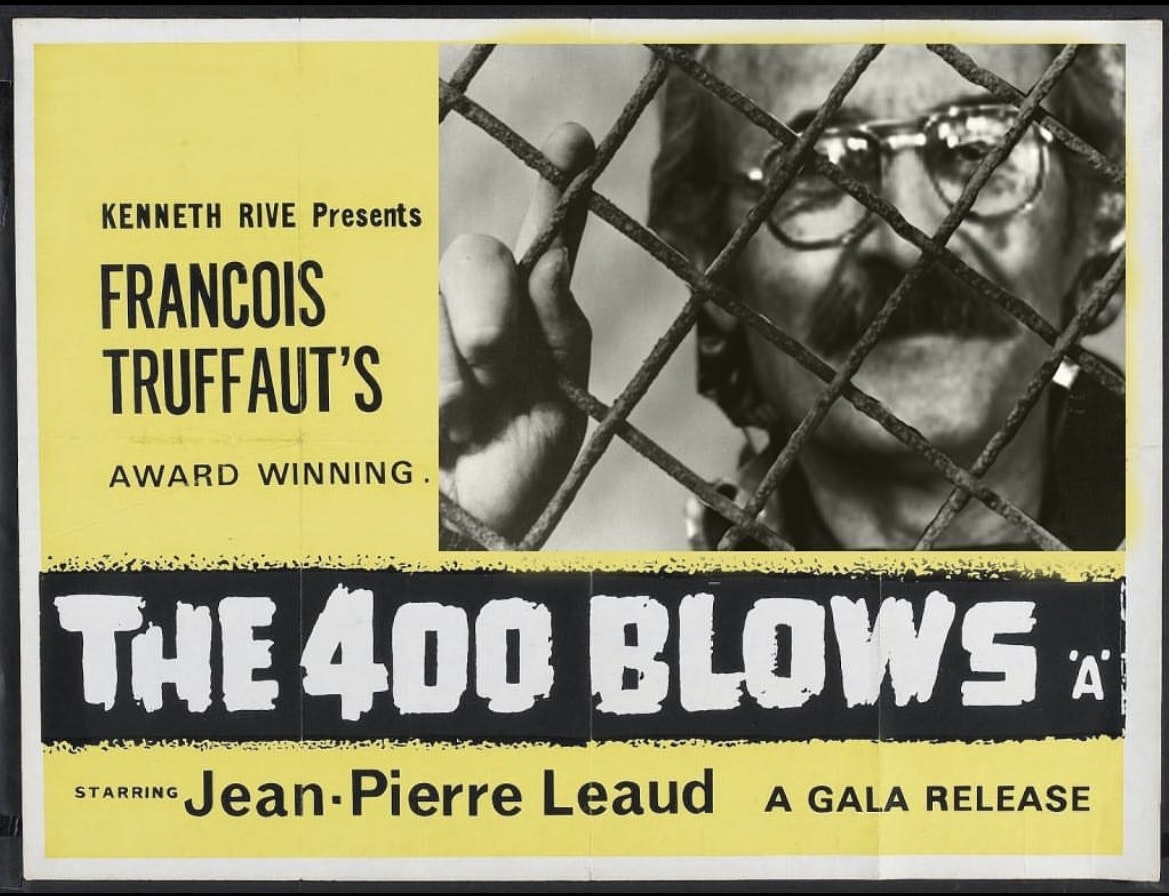

François Truffaut’s sublime autobiographical debut is now rereleased, a portrait of the artist as an unhappy child. He deserved every prize going simply for those heartstopping images of the children’s faces as they watch a Punch and Judy show. The title itself, from faire les quatre cent coups, means to hand out punishment, raise hell, sow wild oats – but this is an ironic upending. Truffaut’s alter ego, Antoine Doinel, is receiving the blows. They rain down on him. Cruelty and humiliation and desperation – and defiance – are this kid’s destiny.

Jean-Pierre Léaud played the 12-year-old lead in this and the five successive Doinel films, a role which was to define his entire life. Like Truffaut, Doinel is a truant, a delinquent, a kid from an unhappy home and a thief: he steals money, a bottle of milk, a typewriter and, most importantly of all, a piece of writing. For a class assignment, he plagiarises, or at any rate paraphrases, a passage from Balzac’s Quest of the Absolute from 1834, about the death of the alchemist Balthazar Claes, repurposing it for the supposed death of his own grandfather. Doinel even has a candlelit shrine to Balzac in the cramped family apartment, which almost burns the place down.

But Doinel has a tyrannical and narrow-minded schoolteacher (veteran player Guy Decomble, resembling Maigret with his coat and pipe) who is nicknamed petite feuille – little leaf – and is a petty little pedant. Instead of applauding Doinel’s good taste and even conceding that this semi-larceny shows audacity and imagination, this man is simply satisfied with his own cleverness at spotting the borrowing and punishes the boy. It is the ultimate mortification.

Doinel knows that his mother, the brassy Gilberte (Claire Maurier), is unfaithful to his jokey, affectionate stepfather Julien (Albert Rémy); he has seen her kissing a man in the street and knows that gifts of money may be involved. So when he pretends that his mother is dead as a bizarre excuse to explain one truancy – a grotesque lie for which Julien comes to school with his still living mother and slaps Doinel’s face in front of his class – it is clearly an act of matricidal wish-fulfilment of some sort. Doinel bunks off school, roaming all around town and of course going to the movies.

But despite what is perpetually written about The 400 Blows, movies are not overwhelmingly important to Doinel. They do not “save” him the way they really did save the young cinephile Truffaut, whose friendship and mentorship with critic and intellectual André Bazin meant that he was spared dire punishment for desertion during national service. Doinel spends more of his time ranging far afield outside the cinema: in real life, in the streets of Paris. But there is one in-joke: his parents take him to the movies to see Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us (which was not actually released until 1961, two years after The 400 Blows).

Maybe Doinel is Truffaut’s alternative-reality version of himself: a self without the redemption of cinema, his abortive Balzac homage standing for the loss of art. With Gilberte’s shrugging permission, Doinel is sent to juvenile detention, put in police custody with grownup criminals and ladies of the night and then the psychological “observation unit” out in the country near the coast.

That brings us to the final, almost apocalyptic scene on the beach, where Doinel has ended up after running away from reform school. We know that he has never seen the sea. So how does he feel on seeing it now the first time? Does it look like freedom to him? Or another blank wall? When Truffaut freeze-frames on Doinel’s face at the very end, it shows him looking careworn and haggard for the first time: the freeze-frame has captured the moment at which the boy has become a man. This is the 401st blow – aimed at us. Peter Bradshaw, Guardian, 2022