PATHER PANCHALI (1955)

PATHER PANCHALI (1955)

Neorealism has always owed more to melodrama than some of its purveyors and admirers are willing to admit, but Satyajit Ray unreservedly acknowledged the influence of the latter in his Apu Trilogy. Starting with 1955’s Pather Panchali, his feature debut, Ray crafted a stark vision of India’s transition into the modern age that still offset its most unvarnished observations with a sense of poetry that lent classical grandeur to intimate storytelling.

When Apu’s father, Harihar (Kanu Banerjee), develops a high fever and perishes near the start of 1956’s Aparajito, Ray initially illuminates the banality of such a commonplace, senseless death by focusing on the priest’s ragged breathing and futile attempts to rally himself. When Harihar asks for some water from the Ganges, though, the adolescent Apu’s (Pinaki Sengupta) sprint to and from the river gives the film an operatic feel, culminating in a dying breath matched to the sudden flight of scores of birds outside. By framing the verisimilitude of neorealism around the emotional beat of a scene, Ray leverages pseudo-objectivity to make his subjective tragedy all the more poignant, leading an audience while letting them think they’re simply seeing reality.

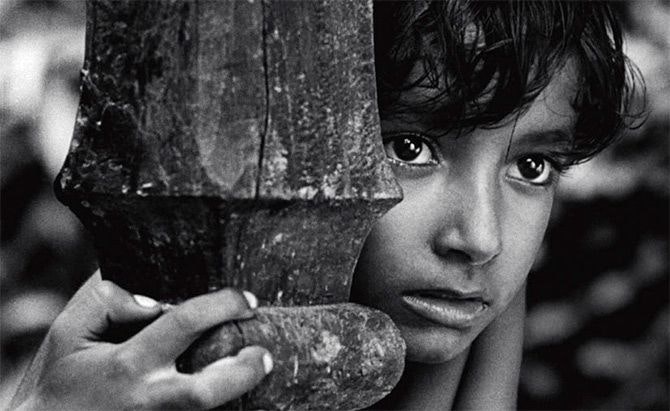

Ray’s control of tone is so great that the films in the Apu Trilogy can often juggle two or more conflicting emotions and explore how antithetical moods can complement each other. The most famous of these would have to be the scene in the first film in the trilogy when the young Apu (Subir Banerjee) and his older sister, Durga (Runki Banerjee), spot a train in the distance while out in a field. They joyfully chase after the locomotive, rushing through reeds taller than them, only to return after their merriment to discover that Harihar’s kind, elderly cousin kind, Indir (Chunibala Devi), has died. Pather Panchali is by and large a story of the loss of innocence, but Ray doesn’t structure the scene as a mere sucker punch to the glee and wonder that precedes it. Instead, he places the tragic with the idyllic to grapple with the contradictory nature of life, never ceding fully to any one emotion to better study natural responses to multiple stimuli.