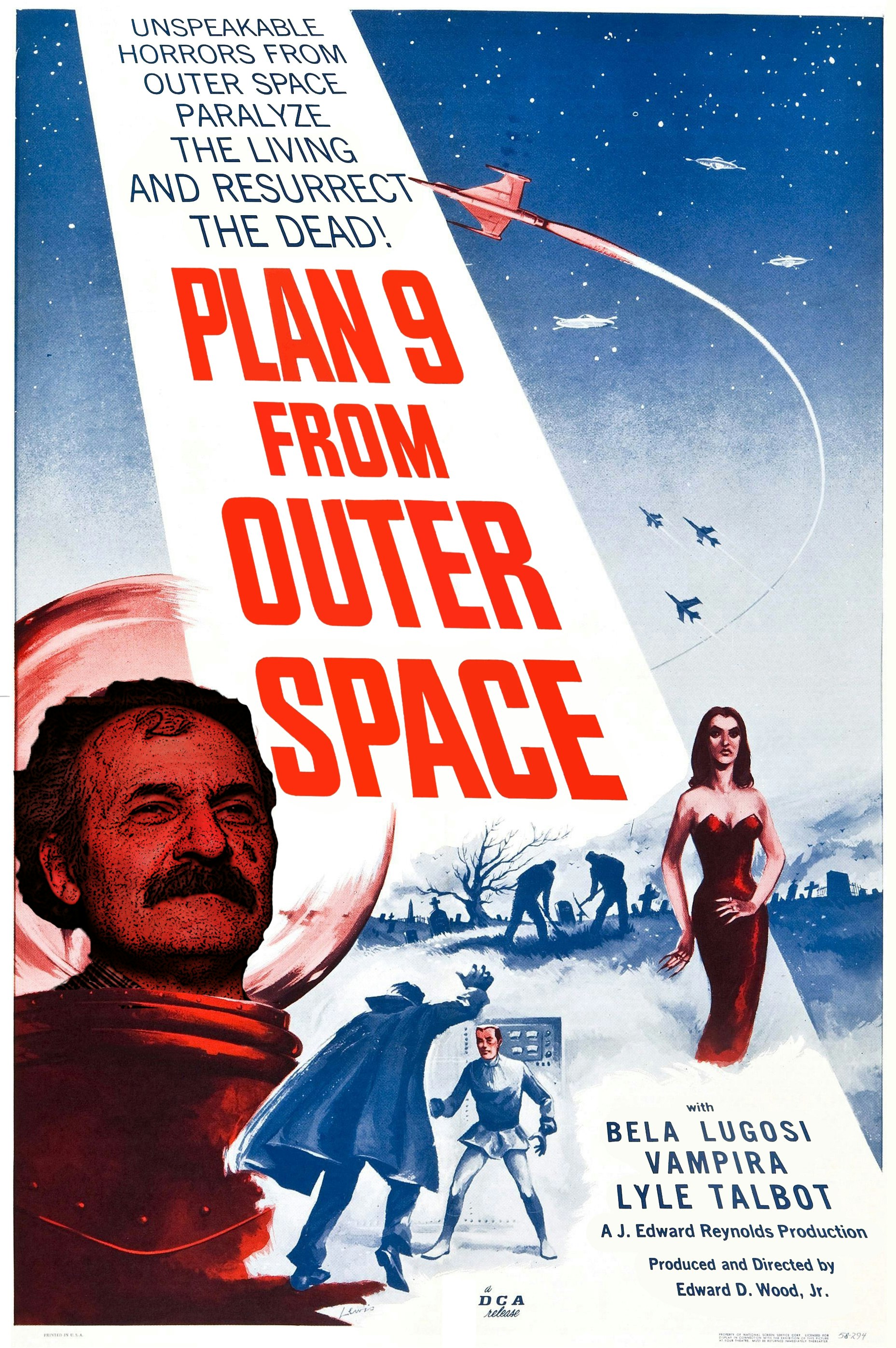

PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE (1959)

PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE (1959)

Edward Davis Wood Jr. died on December 10, 1978. Three days earlier, Wood and his wife Kathy had been evicted from their apartment on the corner of Cahuenga Boulevard and Yucca Street in Los Angeles. Carrying the few possessions they saved from the Dumpster (including an angora sweater and a copy of one of Wood’s final unproduced scripts, I Woke Up Early The Day I Died), the couple found a temporary home with a friend, actor Peter Coe. On the morning of December 10, Wood went into Coe’s bedroom to watch a football game. He never came out.

Kathy Wood later told biographer Rudolph Grey that shortly before Wood was found dead, she heard him calling out to her, complaining that he couldn’t breathe. She ignored his pleas, she said, because “He was always… telling me what to do,” and she figured he was just trying to get a reaction. But Ed Wood was never that good of an actor. By the time someone went to check on him, Wood was dead of a massive heart attack. He was just 54.

Wood’s death certificate is reprinted in Grey’s book, Nightmare Of Ecstasy: The Life And Art Of Edward D. Wood, Jr. It lists his birthdate, his Social Security number, and his cause of death (“arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease”). It also includes information about his career; Wood was self-employed in the “Movie Industry,” a job he’d held for more than 30 years. Curiously, though, in the space for “Primary Occupation” it only names “Writer And Producer”—no mention of his career as a director of more than a dozen Z-grade exploitation and pornographic pictures. Even in death, Wood couldn’t get any respect.

Two years later, Wood finally received some recognition as a director, when The Golden Turkey Awards by Michael and Harry Medved declared him the worst filmmaker in history over the likes of William Beaudine, Herschell Gordon Lewis, and Phil Tucker. The “award” was bad, but the fact that Wood didn’t live long enough to see it—and perhaps profit off his work—was far worse.

In the wake of The Golden Turkey Awards, Wood became the consensus choice for the worst filmmaker ever, but the title doesn’t entirely fit. If there really is a “worst filmmaker ever,” that would be someone who proved too inept to complete a single feature; Wood eked out a living, albeit a meager one, on the outskirts of the film industry for decades. A truly awful filmmaker is a hired gun who only cares about money; Wood was a true cinephile and movie lover, and if he had any interest in financial security, he would have quit the movie business long before his untimely death. The real worst filmmaker ever would produce something no one wanted to watch; many of Wood’s films have been beloved by cultists for decades.

So Ed Wood wasn’t the worst filmmaker of all time. But he might have been the unluckiest. His life story is a series of missed opportunities and broken promises. He would prepare a film, and the financing would fall through. He’d plan a project for an actor, and the actor would die. He finally became famous two years after he died of a heart attack. He made what would become one of the most famous movies in history, then thoughtlessly sold the rights to it for a single dollar to pay his rent.

That film was Plan 9 From Outer Space, which was shot in 1956, but didn’t find its way into release until 1959. It was funded by the Baptist Church Of Beverly Hills in an ill-advised attempt to get into the motion-picture business. One of the church’s leaders, J. Edward Reynolds—Wood’s landlord, who later forgave a debt in exchange for the rights to Plan 9—couldn’t afford to make his dream project, a biopic about Billy Sunday, the famous evangelical Christian minister. Wood, who never let being unable to afford a project stop him from making it, convinced Reynolds to put his meager bankroll behind a science-fiction picture. The plan was to make Wood’s movie, then use the guaranteed profits from its inevitable success to fund the Billy Sunday film. But their plan went awry almost as quickly as the one in the dreadful film they produced.

The first red flag was Wood’s original title: Grave Robbers From Outer Space. Reynolds and his church found the concept of grave robbery sacrilegious, and forced Wood to change the name to Plan 9 From Outer Space. They also demanded that Wood and his crew get baptized, which they did—at a Jewish swimming pool in Beverly Hills. Why Reynolds didn’t also object to the film’s content, which still involved grave-robbing even after the title switch, remains a mystery.

The corpses from the robbed graves become zombies, a particularly fitting choice for a film whose leading man technically gave his performance from beyond the grave. Iconic horror star Bela Lugosi died in August 1956, just after shooting a few test scenes with Wood for a would-be comeback project called The Vampire’s Tomb. When Wood found the funding for Plan 9, he decided to build the entire movie around the Lugosi footage—even though it amounted to less than five usable minutes, none of it involving zombies.

Lugosi plays a grief-stricken man mourning for his late wife (Vampira, because of course Bela Lugosi would be married to a woman who dresses like a vampire). He quickly dies in a traffic accident and gets brought back to life as a zombie. Wood cobbled that much together from the stuff he shot with the real Lugosi. For the rest, Wood employed a body double—his wife’s chiropractor—to play Lugosi’s part. To complete the “illusion,” the man held a cape in front of his face. Why a zombie would wear a cape at all, much less use it to perpetually disguise his identity, also remains a mystery.

These zombies are controlled by the film’s antagonists, meddlesome aliens who arrive from a distant galaxy with a scheme as hilariously misguided as that of South Park’s Underpants Gnomes. Here’s how it works:

Phase 1: Reanimate the corpses of the recently dead, and use them to terrify California residents.

Phase 2: ?

Phase 3: Convince the people of Earth to destroy their nuclear weapons and live in peace.

Can you believe their plan doesn’t work? There are almost no holes in it at all!

Elements like these have made Plan 9 into an enduring favorite among bad-movie lovers for more than half a century. The film’s reputation as the “Worst Movie Of All Time” may be an exaggeration, but not a wild one. Much of the film is indeed awful. The sets are laughably cheap, interiors and exteriors don’t match, and Wood often cuts between day and night shots indiscriminately. With Lugosi dead and an uncooperative Vampira unwilling to do much more than stare menacingly at the camera, he was forced to give much of the early expository dialogue to Tor Johnson, a Swedish professional wrestler, whose English was so garbled, his lines are completely incomprehensible.

Still, Wood might have been better off when the viewers couldn’t make out what the characters were saying. The film is narrated by Criswell, a famous psychic prone to outlandish predictions, and his monologues and voiceovers are laced with amusing contradictions; as he tells it, the film is both about “future events” (“that will affect [us] all in the future”) and based on the “secret testimony of the miserable souls who survived this terrifying ordeal.” (He may, at that point, be speaking about the actors.) Airline pilot Jeff Trent (Gregory Walcott) describes the aliens’ spaceships as “cigar-shaped,” but when they appear onscreen, the ships look like standard-issue UFOs, which means this pilot either has very poor vision, or has never actually seen a cigar before. As the snooty aliens try to convince mankind’s representatives to repent their violent ways, they repeatedly insult their intelligence and “stupid minds.” They might have a point; any species that could create something as dumb as Plan 9 is probably not worthy of atomic power.

It’s hard to argue that Plan 9 From Outer Space is a misunderstood classic; it’d be easier to make that case around Glen Or Glenda, Wood’s deeply personal, intensely surreal essay film about transvestitism and angora fetishes. But there are some ways in which Plan 9 was clearly ahead of its time. It was a zombie movie a decade before George Romero popularized the creatures in Night Of The Living Dead, and it was a conspiracy-theory movie (“These things have been seen for years! They’re here, it’s a fact! And the public ought to know about it!”) more than five years before the Kennedy assassination. Its strange mix of genres (horror and science fiction and detective story and war film) with monsters mixed in (aliens and zombies and vampires) gives Plan 9 the feel of a fan film years before such works became an intrinsic part of popular culture.

Wood himself was ahead of his time as well. While modern fandom was still in its infancy, Wood was already a dyed-in-the-wool fanboy who loved pulp and trash and cast the stars of his favorites (like Lugosi) whenever he could. He was camp before camp was cool, and he made midnight movies before midnight movies existed. Like so many people today, who take to YouTube to document their lives with little to no discernible talent, Wood also felt an insatiable need to express himself—and even expose himself—onscreen. Even though Plan 9 isn’t Wood’s most personal film, it’s still loaded with his fears, frustrations, and obsessions.

Had Wood been born a few years later, he might have become a John Waters-like cult careerist. Like Waters, he loved pushing audiences’ buttons, and he maintained his own stock company of eccentric personalities. If he’d been born a few decades later, he could have been a viral-video superstar, making and promoting his movies outside the mainstream media. Even if Wood lived another 10 years, he would have been able to at least witness and enjoy his ascension to the ranks of the most infamous directors in history. Instead, he died homeless, penniless, and anonymous. It was a sad, stupid (Stupid! Stupid!) end, but a fitting one for one of cinema’s least fortunate trailblazers.