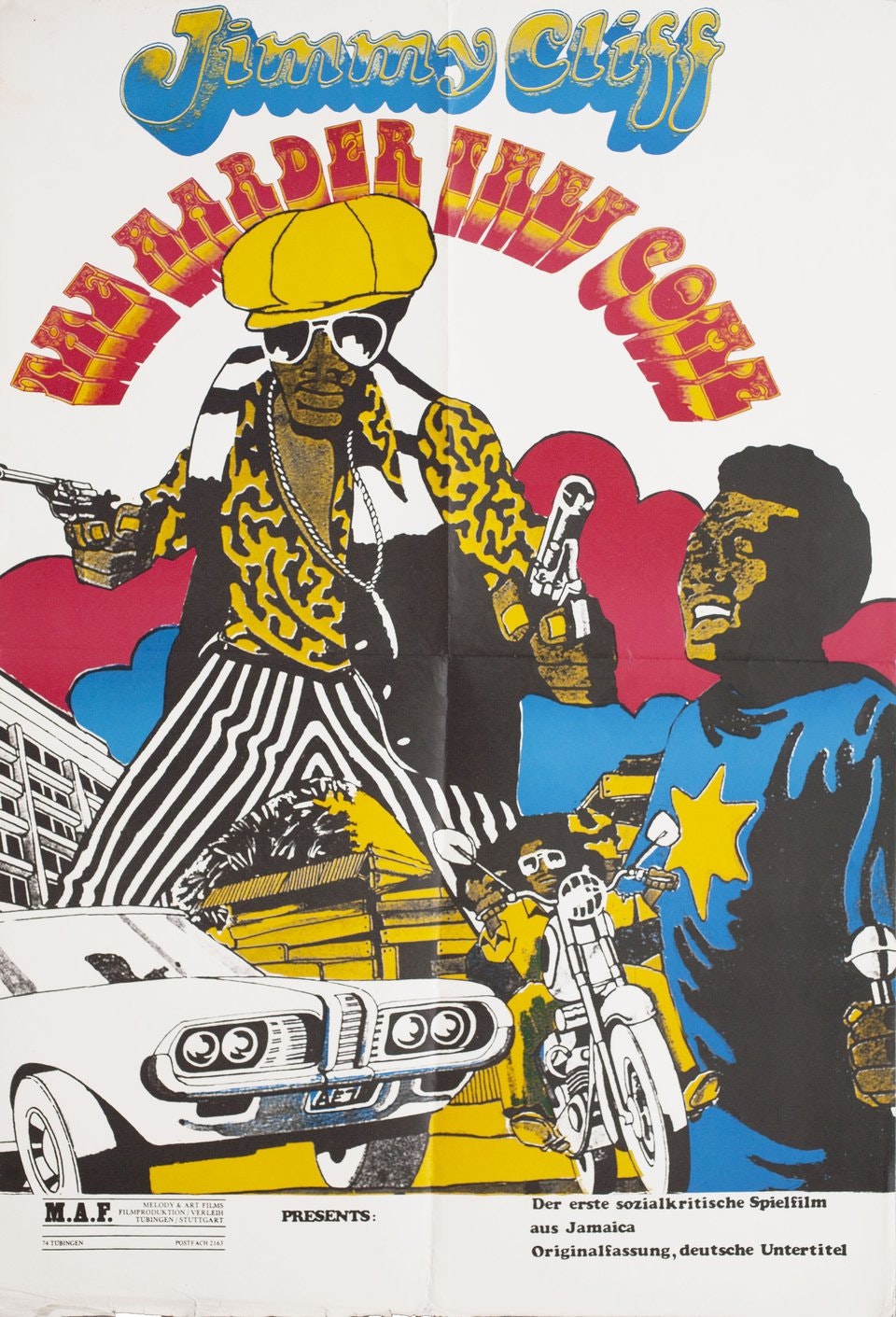

THE HARDER THEY COME (1972)

THE HARDER THEY COME (1972)

A brash bumpkin from the countryside comes to the city, dreaming of stardom. He cuts a record, gets ripped off, turns to trafficking drugs, is betrayed, and dies a folk hero at the hands of the police as his song becomes an anthem.

“The Harder They Come,” is a universal story set in a highly specific milieu. Powered by one of the most infectious scores in the history of cinema, it is also a pop classic — the movie that brought reggae to America and “launched a thousand spliffs,” as the New York Times critic Ben Brantley joked in a 2008 review of a theatrical version in London.

Inspired by the life of the Jamaican outlaw Ivanhoe “Rhygin” Martin, credited with the line that gives the movie its title, “The Harder They Come” was a vehicle for the reggae star Jimmy Cliff. It was independent Jamaica’s first homemade feature, as well as the first film directed by Perry Henzell, a scion of that nation’s white planter class. The distinguished black playwright Trevor Rhone co-wrote the script. (“The Harder They Come” is being shown in conjunction with the theatrical release of Henzell’s long-delayed follow-up, “No Place Like Home,” which is also at BAM.)

Beginner’s luck — or lack of same — might almost be the movie’s subject. Robbed upon arrival in Kingston, Ivan Martin (Cliff) founders at first in the urban maelstrom. Social conditions are manifest in documentary-type shots, filmed in 16 millimeter, of poverty and desperation. Ivan finds his footing only to mix it up with an assortment of predatory preachers, mercenary record producers, corrupt cops and miscellaneous hustlers. In the background, Toots & the Maytals, Desmond Dekker, Cliff and others sing a collective siren song of fame. Chased by the police, Ivan creates his own legend, leaving graffiti (“I am here — I am everywhere”) and imagining an audience for his last stand.

A movie of abrupt transitions, “The Harder They Come” appears to have been assembled piecemeal and shot off the cuff. Cliff, who wrote the title song, has described the film changing direction while in production. In an article published in The Caribbean Quarterly in 2015, the cinematographer Franklyn St. Juste said he never saw a script: “I really didn’t know what was happening — and what was going to happen from one scene to the next or from one setup to the next.” But the spontaneity proved a recipe for what St. Juste termed “happy accidents.”

The timing was also fortuitous. The film arrived on the international scene in the wake of “Shaft” (1971) and “Superfly” (1972), with a hero akin to the righteous outlaws in films like the Brazilian director Glauber Rocha’s “Antonio das Mortes” (1969), Melvin Van Peebles’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971) and numerous Italian westerns. (It’s hardly coincidental that Ivan goes to see “Django,” Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 evergreen.) For early audiences, Ivan’s willingness to defy authority at the cost of his life evoked Bonnie and Clyde, the Black Panthers and Che Guevara.

After making a splash at the 1972 Venice Film Festival, “The Harder They Come” was picked up by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures; it opened (with English subtitles, because of the particularly thick Jamaican patois) to some success at a Broadway theater in February 1973 and enjoyed a second run as an exploitation film. (I saw it that summer in Florida on a double bill with the Pam Grier prison movie “Black Mama, White Mama.”) It would soon have a third life. In a 1974 piece titled “Films That Refuse to Fade Away,” the New York Times critic Vincent Canby noted the movie’s popularity as a midnight attraction.

As reported by Canby, “The Harder They Come” ran for 26 weeks at the Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge, Mass., in 1973. A true cult film, it was brought back in 1974, where, as Jonathan Rosenbaum and I wrote in our book “Midnight Movies,” it remained another seven years. In April 1976, The Times ran an article, noting that “The Harder They Come” had played 80 consecutive weekends at the Elgin Theater in Chelsea. (The run would continue there for months.)

That film’s director, Franco Rosso, named “The Harder They Come” as his inspiration. “Babylon” (1980) might be a sequel, focusing on West Indian life in London. An immersive, verité-style movie following a disaffected young singer of a homegrown reggae group, it uses a constant flow of music to animate the struggle for survival in a hostile white world. “The movie is more interested in what feels right than what seems right,” the critic Wesley Morris wrote in his review for The Times.In his enthusiasm, Canby called “The Harder They Come” “a more revolutionary black film than any number of American efforts, including ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.’” In any case, “The Harder They Come” provided a model for later movies, most notably the 1980 British film “Babylon,”