THE MALTESE FALCON (1941)

THE MALTESE FALCON (1941)

Among the movies we not only love but treasure, “The Maltese Falcon” stands as a great divide. Consider what was true after its release in 1941 and was not true before:

(1) The movie defined Humphrey Bogart's performances for the rest of his life; his hard-boiled Sam Spade rescued him from a decade of middling roles in B gangster movies and positioned him for “Casablanca,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “The African Queen” and his other classics.

(2) It was the first film directed by John Huston, who for more than 40 years would be a prolific maker of movies that were muscular, stylish and daring.

(3) It contained the first screen appearance of Sydney Greenstreet, who went on, in “Casablanca” and many other films, to become one of the most striking character actors in movie history.

(4) It was the first pairing of Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, and so well did they work together that they made nine other movies, including “Casablanca” in 1942 and “The Mask of Dimitrios” (1944), in which they were not supporting actors but actually the stars.

(5) And some film histories consider “The Maltese Falcon” the first film noir. It put down the foundations for that native American genre of mean streets, knife-edged heroes, dark shadows and tough dames.

Of course film noir was waiting to be born. It was already there in the novels of Dashiell Hammett, who wrote The Maltese Falcon, and the work of Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, John O'Hara and the other boys in the back room. “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean,” wrote Chandler, and that was true of his hero Philip Marlowe (another Bogart character). But it wasn't true of Hammett's Sam Spade, whowas mean, and who set the stage for a decade in which unsentimental heroes talked tough and cracked wise.

The moment everyone remembers from “The Maltese Falcon” comes near the end, when Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Mary Astor) has been collared for murdering Spade's partner. She says she loves Spade. She asks if Sam loves her. She pleads for him to spare her from the law. And he replies, in a speech some people can quote by heart, “I hope they don't hang you, precious, by that sweet neck. . . . The chances are you'll get off with life. That means if you're a good girl, you'll be out in 20 years. I'll be waiting for you. If they hang you, I'll always remember you.”

Cold. Spade is cold and hard, like his name. When he gets the news that his partner has been murdered, he doesn't blink an eye. Didn't like the guy. Kisses his widow the moment they're alone together. Beats up Joel Cairo (Lorre) not just because he has to, but because he carries a perfumed handkerchief, and you know what that meant in a 1941 movie. Turns the rough stuff on and off. Loses patience with Greenstreet, throws his cigar into the fire, smashes his glass, barks out a threat, slams the door and then grins to himself in the hallway, amused by his own act.

If he didn't like his partner, Spade nevertheless observes a sort of code involving his death. “When a man's partner is killed,” he tells Brigid, “he's supposed to do something about it.” He doesn't like the cops, either; the only person he really seems to like is his secretary, Effie (Lee Patrick), who sits on his desk, lights his cigarettes, knows his sins and accepts them. How do Bogart and Huston get away with making such a dark guy the hero of a film? Because he does his job according to the rules he lives by, and because we sense (as we always would with Bogart after this role) that the toughness conceals old wounds and broken dreams.

John Huston had worked as a writer at Warner Bros. before convincing the studio to let him direct. “The Maltese Falcon” was his first choice, even though it had been filmed twice before by Warners (in 1931 under the same title and in 1936 as “Satan Met a Lady”). “They were such wretched pictures,” Huston told his biographer, Lawrence Grobel. He saw Hammett's vision more clearly, saw that the story was not about plot but about character, saw that to soften Sam Spade would be deadly, fought the tendency (even then) for the studio to pine for a happy ending.

When he finished his screenplay, he set to work story-boarding it, sketching every shot. That was the famous method of Alfred Hitchcock, whose “Rebecca” won the Oscar as the best picture of 1940. Like Orson Welles, who was directing “Citizen Kane” across town, Huston was excited by new stylistic possibilities; he gave great thought to composition and camera movement. To view the film in a stop-action analysis, as I have, is to appreciate complex shots that work so well they seem simple. Huston and his cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, accomplished things that in their way were as impressive as what Welles and Gregg Toland were doing on “Kane.”

Consider an astonishing unbroken seven-minute take. Grobel's bookThe Hustonsquotes Meta Wilde, Huston's longtime script supervisor: “It was an incredible camera setup. We rehearsed two days. The camera followed Greenstreet and Bogart from one room into another, then down a long hallway and finally into a living room; there the camera moved up and down in what is referred to as a boom-up and boom-down shot, then panned from left to right and back to Bogart's drunken face; the next pan shot was to Greenstreet's massive stomach from Bogart's point of view. . . . One miss and we had to begin all over again.”

Was the shot just a stunt? Not at all; most viewers don't notice it because they're swept along by its flow. And consider another shot, where Greenstreet chatters about the falcon while waiting for a drugged drink to knock out Bogart. Huston's strategy is crafty. Earlier, Greenstreet has set it up by making a point: “I distrust a man who says 'when.' If he's got to be careful not to drink too much, it's because he's not to be trusted when he does.” Now he offers Bogart a drink, but Bogart doesn't sip from it. Greenstreet talks on, and tops up Bogart's glass. He still doesn't drink. Greenstreet watches him narrowly. They discuss the value of the missing black bird. Finally, Bogart drinks, and passes out. The timing is everything; Huston doesn't give us closeups of the glass to underline the possibility that it's drugged. He depends on the situation to generate the suspicion in our minds. (This was, by the way, Greenstreet's first scene in the movies.)

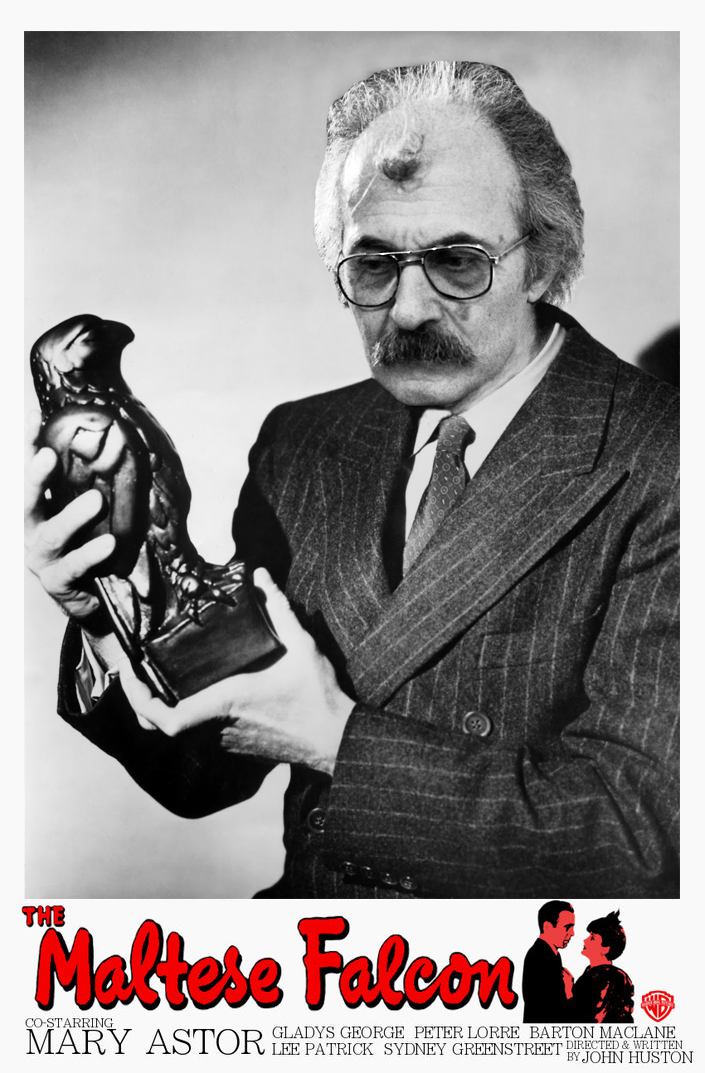

The plot is the last thing you think of about “The Maltese Falcon.” The black bird (said to be made of gold and encrusted with jewels) has been stolen, men have been killed for it, and now Gutman (Greenstreet) has arrived with his lackeys (Lorre and Elisha Cook Jr.) to get it back. Spade gets involved because the Mary Astor character hires him to--but the plot goes around and around, and eventually we realize that the black bird is an example of Hitchcock's “MacGuffin”--it doesn't matter what it is, so long as everyone in the story wants or fears it.

To describe the plot in a linear and logical fashion is almost impossible. That doesn't matter. The movie is essentially a series of conversations punctuated by brief, violent interludes. It's all style. It isn't violence or chases, but the way the actors look, move, speak and embody their characters. Under the style is attitude: Hard men, in a hard season, in a society emerging from Depression and heading for war, are motivated by greed and capable of murder. For an hourly fee, Sam Spade will negotiate this terrain. Everything there is to know about Sam Spade is contained in the scene where Bridget asks for his help and he criticizes her performance: “You're good. It's chiefly your eyes, I think--and that throb you get in your voice when you say things like, 'be generous, Mr. Spade.' “ He always stands outside, sizing things up. Few Hollywood heroes before 1941 kept such a distance from the conventional pieties of the plot.

Roger Ebert