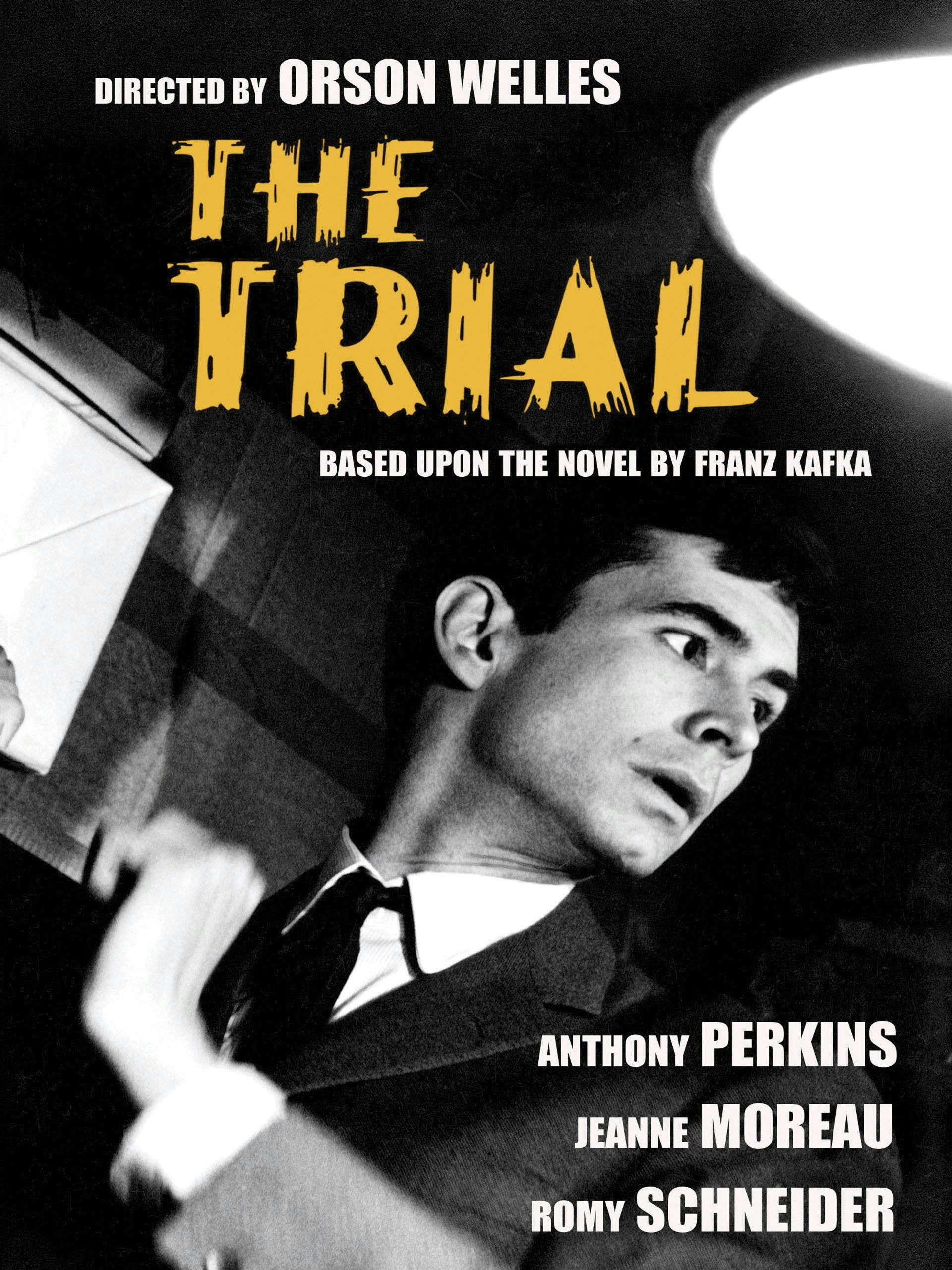

THE TRIAL (1963)

THE TRIAL (1963)

Roger Ebert was once involved in a project to persuade Orson Welles to record a commentary track for "Citizen Kane." Seemed like a good idea, but not to the Great One, who rumbled that he had made a great many films other than "Kane" and was tired of talking about it.

One he might have talked about was "The Trial" (1963), his version of the Franz Kafka story about a man accused of--something, he knows not what. It starred Anthony Perkins in his squirmy post- "Psycho" mode, it had a baroque visual style, and it was one of the few times, after "Kane," when Welles was able to get his vision onto the screen intact. For years, the negative of the film was thought to be lost, but then it was rediscovered, restored and plays at the Film Center this weekend.

The world of the movie is like a nightmare, with its hero popping from one surrealistic situation to another. Water towers open into file rooms, a woman does laundry while through the door a trial is under way, and huge trunks are dragged across empty landscapes and then back again. The black-and-white photography shows Welles' love of shadows, extreme camera angles and spectacular sets. He shot it mostly inside the Gare d'Orsay in Paris, which, after it closed as a train station and before it was reborn as a museum, offered vast spaces; the office where Joseph K works consists of rows of desks and typists extending almost to infinity, like a similar scene in the silent film "The Crowd." Kafka published his novel in Prague in 1925; it reflected his own paranoia, but it was prophetic, foreseeing Stalin's gulag and Hitler's Holocaust, in which innocent people wake up one morning to discover they are guilty of being themselves. It is a tribute to his vision that the word "Kafkaesque" has, like "Catch-22," moved beyond the work to describe things we all see in the world.

Anthony Perkins was a good choice to play Joseph K, the bureaucrat who awakens to find strange men in his room, men who treat him as a suspect and yet give him no information. Perkins could turn in an instant from ingratiating smarminess to anger, from supplication to indignation, his voice barking out ultimatums and then suddenly going high pitched and stuttery. Watch his body language as he goes into his confiding mode, hitching closer to other characters, buddy-style, looking forward to neat secrets.

The film follows his attempts to discover what he is charged with, and how he can defend himself. Every Freudian slip is used against him (he refers to a "pornograph player" and a man in a black suit carefully notes that down). He finds himself in a courtroom where the audience is cued by secret signs from the judge. He petitions the court's official portrait painter, who claims he can fix cases and obtain a "provisional acquittal." And in the longest sequence, he visits the cavernous home of the Advocate, played by Welles as an ominous sybarite who spends much of his time in bed, smoking cigars and being tended by his mistress (Romy Schneider).

The Advocate has obscure powers in matters such as Joseph K is charged with, whatever they are. He has had a pathetic little man living in his maid's room for a long time, hoping for news on his case, kissing the Advocate's hand, falling to his knees. He would like Joseph K to behave in the same way.

The Advocate's home reaches out in all directions, like a loft, factory and junk shop, illuminated by hundreds of guttering candles, decorated by portraits of judges, littered with so many bales of old legal papers that one shot looks like the closing scene in "Citizen Kane." But neither here nor elsewhere can Joseph K come to grips with his dilemma.

Perkins was one of those actors everyone thought was gay. He kept his sexuality private, and used his nervous style of speech and movement to suggest inner disconnects. From an article by Edward Guthmann in the San Francisco Chronicle, I learn that Welles confided to his friend Henry Jaglom that he knew Perkins was a homosexual, "and used that quality in Perkins to suggest another texture in Joseph K, a fear of exposure."

"The whole homosexuality thing--using Perkins that way--was incredible for that time," Jaglom told Guthmann. "It was intentional on Orson's part: He had these three gorgeous women (Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Elsa Martinelli) trying to seduce this guy, who was completely repressed and incapable of responding." That provides an additional key to the film, which could be interpreted as a nightmare in which women make demands Joseph K is uninterested in meeting, while bureaucrats in black coats follow him everywhere with obscure threats of legal disaster.

But there is also another way of looking at "The Trial," and that is to see it as autobiographical. After "Citizen Kane" (1941) and "The Magnificent Ambersons" (1942, a masterpiece with its ending hacked to pieces by the studio), Welles seldom found the freedom to make films when and how he desired. His life became a wandering from one place to another. Beautiful women rotated through his beds. He was reduced to a supplicant who begged financing from wealthy but maddening men. He was never able to find out exactly what crime he'd committed that made him "unbankable" in Hollywood. Because Welles plays the Advocate, there is a tendency to think the character is inspired by him, but I can think of another suspect: Alexander Salkind, producer of "The Trial" and much later of the "Superman" movies, who like the Advocate, liked people to beg for money and power that, in fact, he did not always have.

Seen in this restored version (also available on video from Milestone), "The Trial" is above all a visual achievement, an exuberant use of camera placement and movement and inventive lighting. Study the scene where screaming girls chase Joseph K up the stairs to a studio and peer at him through the slats of the walls, and you will see what Richard Lester saw before he filmed the screaming girls in "A Hard Day's Night" and had them peer at the Beatles through the slats of a railway luggage car.

The ending is problematical. Mushroom clouds are not Kafkaesque because they represent a final conclusion, and in Kafka's world nothing ever concludes. But then comes another ending: The voice of Orson Welles, speaking the end credits, placing his own claim on every frame of the film, and we wonder, is this his way of telling us "The Trial" is more than ordinarily personal? He was a man who made the greatest film ever made and was never forgiven for it.