VERTIGO (1958)

VERTIGO (1958)

The unbearably sad, exquisitely macabre love story that is Vertigo now reaches its 65th birthday, and this week sees its rerelease, not much liked on first appearing in 1958 but now hugely canonical and prestigious, due very much to unending critical interest in “the male gaze”, pioneered by theorists such as Michel Foucault and Laura Mulvey. This is that act of seeing that, so far from being transparent and neutral, is an imposition of power, and therefore extremely applicable to this drama of obsession and voyeurism, although I never tire of pointing out that there are very few members of the hetero-patriarchy who have the confidence or fanatical connoisseurship to pick out a woman’s clothes or exactly specify her hairstyle. Vertigo also combines in an almost unique balance Hitchcock’s brash flair for psychological shocks with his elegant genius for dapper stylishness. Like Psycho, it ends in an “o”, or maybe “oh!” The ancient house adjoining the Bates motel in Psycho certainly has an unearthly similarity to San Francisco’s creepy old McKitterick Hotel in Vertigo.

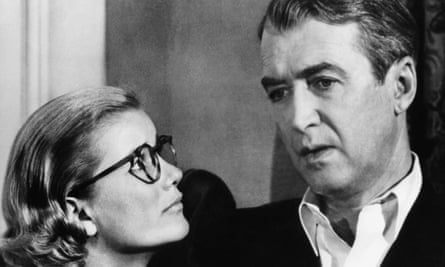

James Stewart plays ex-cop Scottie, invalided out of the police due to vertigo brought on by a traumatic and shaming calamity during a rooftop chase. He is hired by old schoolfriend Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) for a strange job: to shadow his beautiful and enigmatic wife Madeline (Kim Novak) whose behaviour is worrying him. This bizarre situation unlocks lonely Scottie’s gallantry and romanticism and he falls passionately in love with this mysterious, troubled woman with her quiet, wondering voice and the manner of a sleepwalker. And later, when his vertigo prevents him from stopping another disaster, Scottie is to fall in love with another woman, Kansas-born Judy Barton, who has an eerie similarity to Madeline. With fanatical dedication, Scottie forces Judy to dress and sound like his lost love.There are two ways of approaching Vertigo. One is to see it as a male film on the side of the male view of women; the other is to see it as a satirical attack on the misogynist mindset. They are, in fact, two sides of the same interpretative coin. The imaginative sympathies and dramatic voltage are wired up to Scottie’s anguished point of view. (Actually, Hitchcock did make a film from the viewpoint of the woman, the female gazee, forced by a controlling man into the shoes of his obsessed-over first love – Rebecca.)

One of the film’s most brilliant moments concerns Scottie’s platonic pal and ex-girlfriend Midge Wood (Barbara Bel Geddes), a commercial artist in whose messy bohemian apartment Scottie is in the habit of hanging out. Midge crucially wears glasses, the sort that in other circumstances might be removed by someone saying: “Why Miss Wood, you’re beautiful!” These glasses are there to make her less attractive and signal that she is not the movie’s romantic interest, but also that she herself is a seer, a gazer – noticing from afar evidence of Scottie and Madeleine’s affair with a wry smile, but also perhaps a twinge of the heart.

Inspired by Scottie telling her about Madeleine’s own trance-like obsession with a 19th-century portrait of a beautiful tragic ancestor, Midge paints herself in the same pose: glasses and all. When he sees it, Scottie winces. So do we, the audience. The pure wrongness is shocking: smart, wry, detached Midge is completely wrong in the role. The portrait has to be of someone infinitely, demurely, fatally passive and gazed upon – not a humorous, intelligent woman with her own visual judgment and indeed her own job.

The Freudian images are everywhere in Vertigo, and not simply in the showstopping dream sequences or the nightmarish light-filter changes bringing out the hypnotic pale blue of Stewart’s eyes. The “brassiere” or bra that Midge is drawing for an ad is cantilevered, she says, like a bridge – thus associating the famous Golden Gate Bridge scene with a woman’s underwear. (When Scottie brings Madeleine back to his apartment after saving her from drowning, he undresses her and puts her in bed while she is still unconscious: although perhaps he left her underwear in place. It isn’t clear.) The tower could be phallic, and the nestling nosegay of flowers that Madeline buys is also emblematic of something, though not as obviously as the tight whorl of hair at the back of her head: a mesmeric circle (again, like bloody water circling a drain) or an orifice of some sort.

When I watched this again, I felt more strongly than ever that Hitchcock’s decision to give us a story in which the Clouzot-esque twist is given away well before the end is no misjudgment. It is a brilliant way of putting us inside Judy’s tormented, guilty soul, and of avoiding, just for a while, that male gaze. I also realised what it is Vertigo has been subtly reminding me of for many years: Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. A treat to see this back on the big screen.

Peter Bradshaw